Agriculture, Education December 01, 2024

Farming Today's Alaska

Boom or bust, there's no cooling the pioneering optimism of Alaskan producers.

by Martha Mintz

Everything may be bigger in Texas, but the nation's actual largest state could rightly adopt the motto, 'Everything is more difficult in Alaska.' It's a maxim certainly applicable to farming in a state known for its extremes.

That hasn't stopped the determined individuals who farm the challenging landscape. Promises of plentiful and affordable land and state-funded farm projects have encouraged influxes of hopeful farmers to Alaska at various points in history.

While plenty of Alaskan farms have gone bust, there's been steady growth in Alaska's ag sector. Skilled farmers who saw potential and were determined to tap it fought forward while support and funding ebbed and flowed.

Optimism for Alaska's agricultural potential is once again on the rise. State lands are being auctioned for agricultural development, food security is driving favorable legislation and funding, even the climate is cooperating.

"The climate in Alaska is warming rapidly, leading to a longer cropping season," says Jakir Hasan, University of Alaska Fairbanks (UAF) research assistant professor of plant genetics.

This could mean an expanded roster of crops able to be grown in Alaska, including wheat.

"The search for a spring wheat variety that can thrive in Alaska has been ongoing for over 200 years," Hasan says. The UAF small grains breeding program has been working diligently since 2022 to develop varieties suitable for the anticipated increase in rainfall and growing degree days in the coming decades. The first adapted spring wheat variety may be in fields within the next 6 to 8 years. "It's a significant milestone in the history of wheat cultivation in Alaska," Hasan says.

These are all tantalizing motivators for those looking for a way to break into farming. It's a path already well traveled.

The farming veterans. Alaska was the answer when Mike Schultz's family needed to expand their Iowa farm in the 1980s.

"There was no way we could get a land purchase in Iowa to pencil out," Schultz says. Interest rates had surpassed 20% and farmland was selling for $3,000 per acre. Iowa wasn't in the cards.

Instead, Schultz and his brother Scott bought 1,883 acres at auction near Delta Junction, Alaska. The land was part of the state-funded Delta land project aiming to increase agricultural production.

The brothers navigated shifting markets and lacking infrastructure to succeed. Over 40 years they grew their farm to 8,000 acres. They now harvest around 3,000 acres of barley, grass seed, and forage annually. Growth was possible as other landowners left the area or retired without anyone to take over.

The large acreages and shrinking farming community of the Delta project aren't representative of where Alaskan agriculture is headed as a whole, however.

Each USDA Ag Census since 1997 recorded a steadily increasing number of farms. Over the same period farm size steadily decreased dropping to 742 acres in 2022 from 1,608 acres in 1997.

The number of small Alaskan farms may continue to climb as the state fixates on food security.

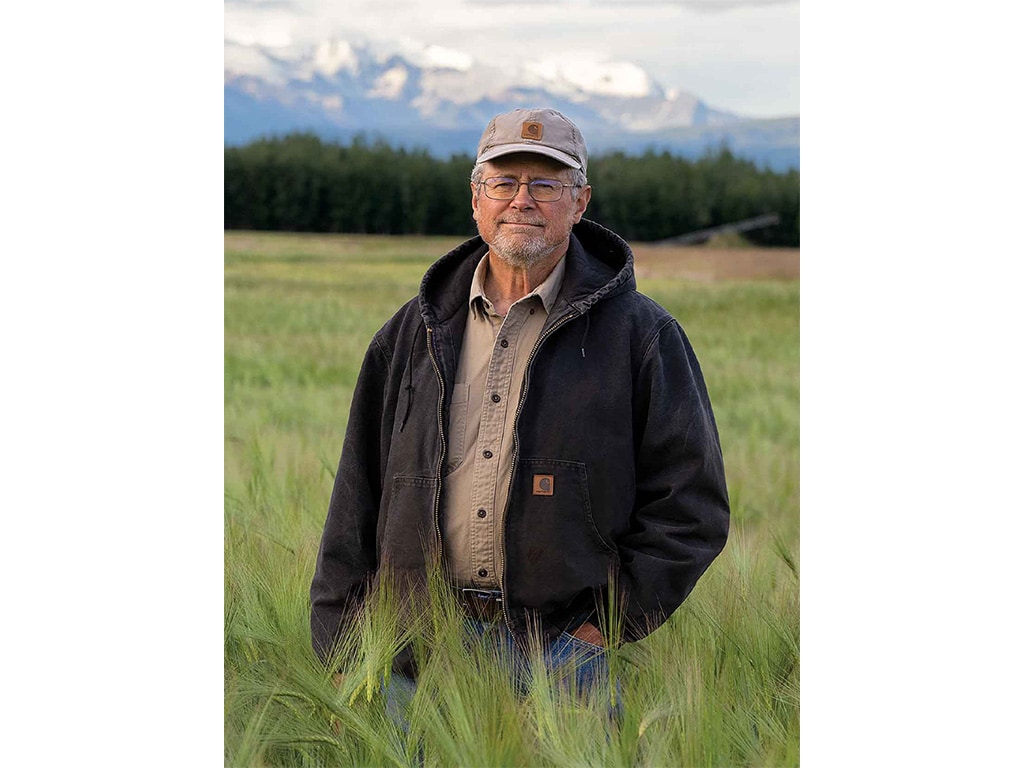

Above. Scott Mugrage and his grandson Eli chat with Hayden. His father works for Mugrage on his hay and cattle operation. Keeping good help is an ongoing challenge. Mike Schultz has racked up 40 years of Alaska farming. The newly cleared land of Alaska's newest ag project may one day match the established Delta project fields. Wood mulch litters the ground in Coffey's new field in Alaska's Nenana-Totchaket Ag Project. Crops thrive where brush piles burned, revealing fertility as a critical need. Adrianne Coffey (in blue) helps Alaska FFA members spot developing ears. The Coffeys are trialing many crops as they work to bring their new land into production. Glenna Gannon (right), UAF assistant research professor, conducts variety trials to identify cultivars that perform best in the evolving Alaskan climate. A lengthening growing season merits giving traditionally marginal crops like peppers, tomatoes, and corn a second look. Naomi Broderson grows peonies, one of Alaska's limited export crops.

Driven to independence. According to the Alaska Food Security Task Force, 95% of purchased Alaskan food is imported at a cost of around $2 billion per year.

This statistic was critically felt when the pandemic interrupted supply chains. Food security has been cited heavily in policy development, legislation, and funding decisions ever since.

Food security was listed as a driving force for the Alaska Department of Natural Resources moving forward with the Nenana-Totchaket Agricultural Project after it sat idle for decades.

Like the Delta project, the region was identified for agricultural development in the 1970s. A bridge was finally constructed in July 2020 to facilitate access to the land. In fall 2022, the first parcels of raw land were auctioned for agricultural development.

Raw being the key word.

In the Alaskan Interior, trees and brush own the landscape. Clearing the land and conditioning the soil for agricultural production is a long, daunting, and expensive process.

Access to affordable, productive land is at the forefront of concern for Alaska's Beginning and Young Farmers Network, according to farmer and member Sam Knapp.

"It's really difficult to find cleared land that's close to a market and something you can actually afford," he says, noting that a lot of land once cleared for farms around Fairbanks and other historic farming areas has been lost to housing development.

Despite the challenge, Alaska is a magnet for beginning farmers. They make up 38.7% of Alaska's farming community. Only Rhode Island boasted higher numbers.

The Knapps got their farming start when they purchased a largely undeveloped acreage near Fairbanks in January 2020. They've cleared the land themselves, incrementally increasing production of winter-storage crops including beets, cabbage, carrots, onions, and turnips.

The Knapps have enjoyed strong demand. Selling winter CSA subscriptions was possibly the easiest part of establishing Offbeet Farm, Sam says.

The Alaska Farmers Market Association reported 62 markets operating in 2022, up from just 13 in 2005. Data from 14 of those markets reported $2.5 million in sales.

"I think there's a lot of opportunity for new farmers here and I welcome them," Sam says.

Just an hour away in Nenana, Adrianne and Tarn Coffey are also anticipating marketing to be the easiest part of their new farming venture. The Coffeys purchased five of the Nenana-Totchaket Agricultural Project parcels in the fall of 2022.

They've moved quickly to clear the most promising acres and start experimenting with crops.

"Everything we've seeded has been on a trial basis other than the sweet corn," Adrianne says.

Using their garden in nearby Nenana to trial varieties since 2015, the Coffeys identified a 72-day sweet corn variety that works in their area. They're using their new farm to scale up production.

It will be a slow process. The 2024 corn crop was highly variable. There were hiccups with planting as the Coffeys learned to operate their new farm equipment.

Fertility is another challenge. Crops thrived where brush piles were burned, but struggled everywhere else. Still, come late August, there were ears to harvest.

The Coffeys take it as a win, well aware it will likely take years of trial and error to dial in production.

"We don't have access to a lot of help," Adrianne says, referring to resources like research and agronomists as they're in uncharted waters both with land and crops. As first to the field, the Coffeys do look forward to sharing what they learn with their neighbors who aren't as far along.

Room to grow. Scott Mugrage found himself in Alaska because he's a trader unable to pass up a good deal or a challenge. Alaska delivered both.

His son, Justin, showed him a run-down Alaskan game farm for sale online in May 2013. That September they were pulling their trailer up the driveway of their new Delta Junction farm.

"I could see so much potential here that wasn't being tapped," Mugrage says. The longtime Nebraska cattle feeder set out at a furious pace. "I found out you can't make change happen quickly."

Change is possible, though. He and Justin transitioned the farm to no-till, swapped in cover crop mixes for fallow in small grains rotations, and proved they could finish cattle year-round without indoor feeding facilities.

Infrastructure bottlenecks are the source of his frustration.

"We built up to 1,500 head on feed and hit a wall because there weren't enough slaughterhouses to handle the capacity," he says.

Some producers have resorted to developing their own processing facilities for their crops.

Bryce Wrigley, another Delta Junction producer, opted to open his own flour milling facility for his hulless barley.

When his restaurant customers faced a labor shortage limiting their ability to use his flour, he and his son Milo, built their own bakery.

Not everyone has that drive or skill set. Mugrage has sought to pursue collaborative solutions in part through his work as president of Alaska Farm Bureau.

"There are indications the future for agriculture here could be really big. As farmers, we're decades away from being each other's competition. We might as well work together," Mugrage says. ‡

Read More

AGRICULTURE, EDUCATION

High on the Hog

Patience turns Spanish ham into gastronomic art.

AGRICULTURE, SPECIALTY/NICHE

A Taste of Place

Vasilos Gletsos' beer provides—literally—a taste of rural Vermont.