Agriculture, Sustainability December 01, 2024

For Greater Good

Buffers, pollinators, and bioreactors reduce nutrient runoff.

by Bill Spiegel

Roughly 1.5 million acres make up the watershed that supplies drinking water for hundreds of thousands of residents in and around Cedar Rapids, Iowa.

The 670 acres Dan Voss farms in that area is a drop in the bucket.

But the Atkins, Iowa, farmer is a proponent of farming practices that reduce soil erosion and nitrates in groundwater, simply because it's the right thing to do.

In 1988, Dan and his dad began using no-till, and converted to strip-till by 1997. The pair established waterways to eliminate concentrated flow erosion areas within fields. After corn harvest, Dan has adopted cover crops including cereal rye and camelina. He also grows oats and alfalfa, crops that pump more carbon into the soil and add diversity.

"A corn and soybean rotation is a hard system to run and still save your soil," Voss explains. "With no-till or strip-till plus cover crops, you can actually improve your soil."

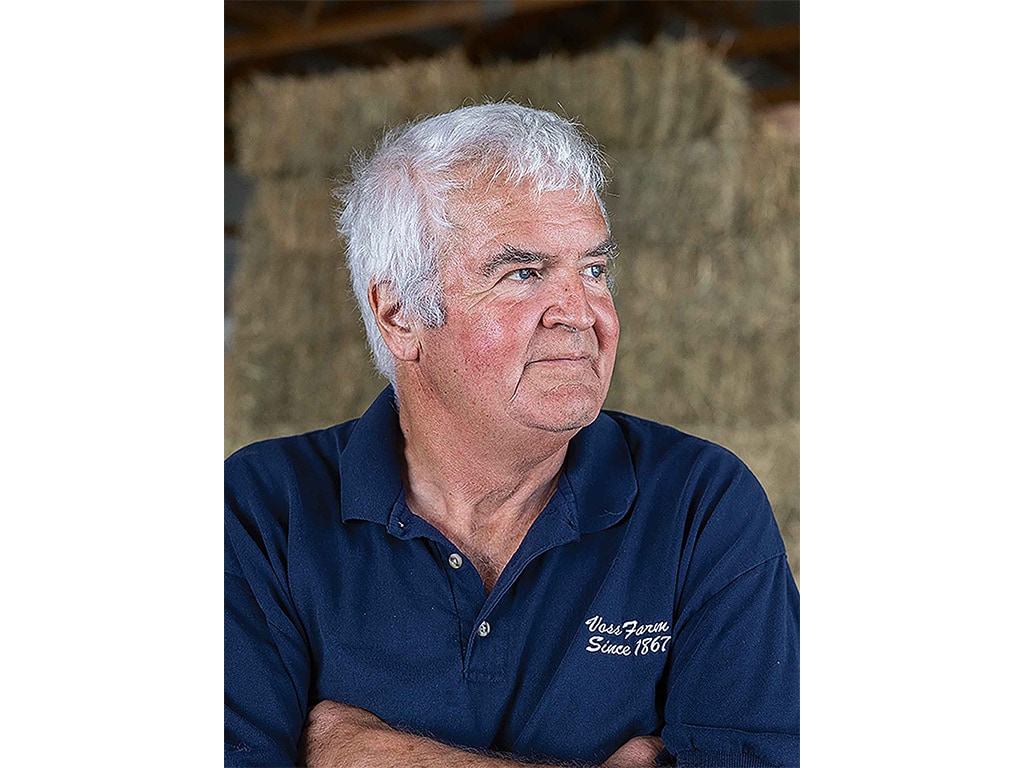

Above.For decades, Iowa farmer Dan Voss has built conservation practices to reduce erosion and improve water quality. Among them: three bioreactors, which use hardwood chips to trap nitrate from entering the groundwater supply. Prairie strips provide pollinator habitat and serve as a buffer along roadsides.

Practices in play. In 2016, Voss signed up for Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP) funding to reduce his out-of-pocket costs on installing some of the enhancements, like saturated buffers and prairie strips on field edges, which provide pollinator habitat.

In 2021, he and other area farmers built bioreactors using "Batch and Build" funding, which allocated a pot of money enabling farmers to build several similar structures in the watershed.

A bioreactor is a lined pit, filled with a carbon source, like hardwood chips, that filters out nitrate from field drainage tile discharge flowing into the pit. The NRCS estimates an average bioreactor can remove 35 to 50% of the nitrates from water flowing through it. On select fields, Voss has installed saturated buffers, areas of permanent vegetation that slow the discharge of tile-drained fields and reduce nitrates from drain water. It's hard to quantify the impact Voss's practices have made on such a large watershed, let alone the 7,000-square-mile hypoxic zone in the Gulf of Mexico, which scientists believe is caused in part by nitrogen fertilizer runoff in the Mississippi River Basin.

"But here's how I think: Anything you can do to help the cause. Because it's not just about Cedar Rapids. It's about all the way down the Mississippi River to the Gulf of Mexico," he explains.

Water quality is the end-game, but Voss says he is saving money, too. Not only has soil organic matter improved, but erosion loss is minimal, and his fields require less synthetic fertilizer and herbicides.

Little by little, area farmers are beginning to embrace these practices, says Jim O'Connell, Voss's neighbor and fellow water quality champion. O'Connell adds that Voss is on the front line of preserving groundwater quality.

"Dan is such an advocate for environmental practices, and does a fantastic job of getting the word out," he says. "He has made a great impact."

Urban impact. In 2023, the city of Cedar Rapids formed the Cedar River Source Water Partnership, a collaboration with the USDA NRCS, that provides funding for farmers to adopt innovative practices to improve water quality.

Officials in the city of 130,000 people stress that drinking water is safe, but nitrate levels have crept up over time.

"Cedar Rapids is the largest corn processing city in the world, which does farmers around here a world of good. Those facilities want clean water," says Voss, who in 2023 earned the Iowa Conservation Farmer of the Year from the Iowa Farm Bureau and the Iowa Department of Agriculture and Land Stewardship.

But Voss doesn't adopt these practices for the accolades. He has an eye on preserving the farm for the sixth and seventh generations: his son Brian and wife Nicole, and the couple's young daughter.

"We're losing topsoil above replacement rates," Voss told Practical Farmers of Iowa. "And I want to do my part in slowing that process down." ‡

Read More

AGRICULTURE, EDUCATION

Legacy Wheat

How Turkey Red changed American agriculture.

AG TECH

Tech@Work

Enhancing the future of farming efficiency through Precision Ag Essentials.