Specialty/Niche December 01, 2024

A Sport of Beauty

Grace, athleticism...and a cloud of dust.

by Katie Knapp & Steve Werblow

Trumpets blare and hooves thunder, kicking up dust and clods as a phalanx of fuchsia-clad riders and their horses charge toward spectators perched on wooden bleachers. Just a few feet from slamming into the wall, the horses flare to a halt and the riders line up to salute the audience.

The riders break left and right into a pair of columns, galloping inches away from the curved arena walls, then darting toward the center. They pass each other at high speed, weaving in and out, their paths bursting like fireworks and pulling together like zippers. The women lean back as their horses pinwheel in tight turns, then bolt into a full run.

The voice of the announcer rises on the loudspeaker as the riders fall into a hard-charging formation, just inches apart. They pivot toward the back of the arena and in moments, the dazzling horses, riders, and shoulder-width sombreros are just shadows in a cloud of brown dust.

That cloud of dust goes right back to the start of "escaramuza," which translates to "skirmish"—it was one of the diversionary tactics female riders used during the Mexican Revolution to help give insurgents an advantage over federal troops. Out of the women's dusty smokescreens and brave decoy maneuvers in Mexico's 1910-to-1920 conflict, a sport was born.

Escaramuza is a stunning display of riding skill, strong horses, and strong women riding sidesaddle bolt upright. Fast as barrel racing and precise as ballet, escaramuza links horse to rider, and teammate to teammate, through trust and communication. It's about speed, skill, and pride.

Moving north. Escaramuza riding events began in the 1950s, but were not official elements of Mexican and American charrería—or Mexican-style rodeo—until official recognition in 1991.

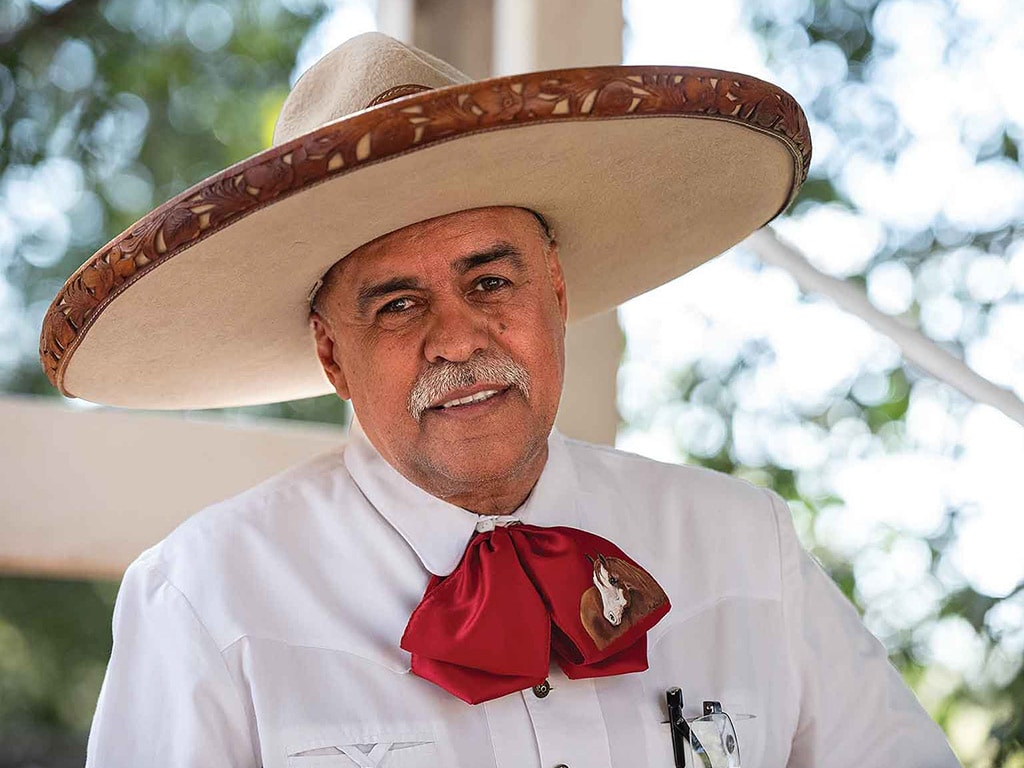

Edmundo Rios II, president of the San Antonio Charro Association in Texas, figures 50 to 60 U.S. teams currently compete in escaramuza competitions. Eighteen U.S. states belong to the American Charro Association, he adds.

Each 8-woman escaramuza team—including San Antonio's Las Coronelas—is vying for a spot at Nationals and the chance to compete in the top annual competition in San Luis Potosí, Mexico.

Every competition is tough and exacting. Teams choreograph elaborate routines that highlight each of 12 compulsory skills. As they execute turns, ladders, crosses, and stars, they are judged on speed, precision, and more.

"They're judged on the timing of the horse—it's got to be perfect," Rios points out. "They get points on how they're sitting, their posture, everything."

"And everything has to be the same on each horse," he adds. "They've got to have the same dresses, the same saddles, cinchos [belts], whips, everything's got to be identical."

The precision of it all is thrilling, according to Itziry Pliego, a 21-year-old member of one of the newest U.S. teams, Escaramuza Las Coronelas De Minnesota.

"It's like having a twin out there," she says. "Keeping eye contact with the other girls as you close the cruces, the horse's head passing right behind the other's tail, is probably the hardest part of being in escaramuza." (A cruce is a required skill where the horses cross in front of each other.)

Pliego's parents are the reason she jumped in the saddle sideways and finds so much joy in gracefully holding her shoulders and sombrero brim level as her horse gallops and dances beneath her. Before moving to Minnesota—an area better known for its historic Scandinavian heritage than today's vibrant Latino culture—her parents were charros, or traditional riders, in Mexico.

"It feels really good that we are bringing some Mexican culture to people here," Pliego says as emotions start to bubble up.

The attention has gone global. In 2018 UNESCO recognized charrería as a piece of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

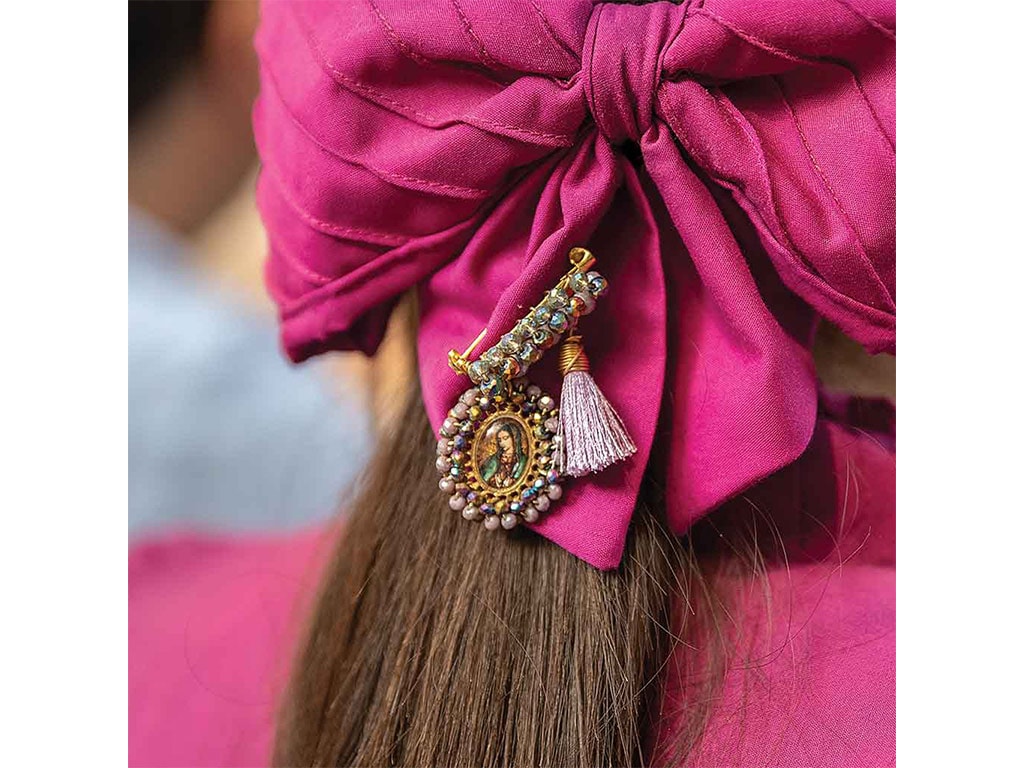

Above. Each lady rides sidesaddle during an escaramuza performance. By day, Ana Lucia Camacho Sevilla is the Mexican state of Jalisco's Secretary of Agriculture and Rural Development. By night and on weekends, she carries on a proud precision riding tradition with her escaramuza team, La Quinta San Francisco. Announcer Ramiro Ramírez Arriola, helps build excitement for the action-packed escaramuza performance. Each charra (female rider) adorns herself with symbols of her faith to keep her calm and protected. Escaramuza celebrates the dust clouds and diversions created by brave female riders during the Mexican Revolution. Ximena Navarro López smiles broadly as the adrenaline starts to drain from her veins following a performance in Tequila, Mexico. She only started riding and performing in the La Quinta San Francisco escaramuza team in 2022. She says joining her family members in this sport has helped her grow in many ways.

Finding footing. Pliego's team is just finding its footing. After being featured in the local newspaper, they have seen a rush of interest in their every-other-week performances.

"People now come to charrerías just to watch our escaramuza [as opposed to the men's events]. They are even asking how they can join our team. It makes us feel special and that we are doing something good to keep the cultural pastime alive" she adds, still in shock over their rising popularity. The team's name, and that of many others, includes the term for women who became rebel officers during the Mexican Revolution.

Rios and the riders of the San Antonio team find the same attention true in their area and work hard to share charrería—including escaramuza—with the community. They invite the public to practices and competitions, host events, and participate in a wide range of festivals and celebrations across the city.

"We try to educate everybody on our tradition," Rios says. "It's a beautiful tradition. It's family-oriented. It's the pageantry, the colors that they use, the way they ride. It's just beautiful."

What they wear during the event holds as much cultural significance as the choreography. Their outfits, fully adorned in heirloom Madonna brooches and layers of ruffles, are patterned after the outfit said to be worn by a legendary fighter in Pancho Villa's army named Adelita.

In fact, escaramuza riders are often called Adelitas. Unlike the distinctive regional dresses worn in each of Mexico's states, escaramuza teams across Mexico and the U.S. generally sport the same style—layered Adelita dresses, shawls, and sashes tied in huge butterfly bows. Design, fabric, and color are carefully defined in a set of detailed rules.

Riders also wear ornate jewelry depicting Catholic motifs and saints to help keep them in the right frame of mind.

"We each wear a small escapulario around our neck with the Lady of Guadalupe on it to protect us during our routine," Pliego explains.

Now it's a friendly dust-up. After the Mexican Revolution in the early 20th century, the events now part of a charrería became common activities on farms and ranches near Jalisco, a state in west-central Mexico. Those riding, roping, and team drill moves are still as big a part of the area's culture as the sombrero brims are wide and outfits are elaborate.

Jalisco's current Secretary of Agriculture and Rural Development, Ana Lucía Camacho Sevilla, has performed in an escaramuza team called La Quinta San Francisco for the past three years.

After an exhilarating seven minutes of meticulously executed turning, crossing, running, and stopping in front of spectators gathered around the area behind the Don Roberto tequila distillery in their home state, Camacho said what she likes most about escaramuza is how it highlights Mexican women, that it combines their heritage, poise, and athleticism.

A successful escaramuza team, to Camacho, needs to share certain passions: for animals, traditions, and sport. She adds that each charra needs to wear her "Mexican-ness with pride."

The ladies of La Quinta San Francisco believe the reason they can be so in sync with each other and dazzle their audiences while appearing calm, cool, and collected isn't just because they are family. It is because they are all equals. Camacho says neither age nor time spent in the saddle matters. When they enter the ring, there is no leader. They are all in it together.

La Quinta San Francisco member Ximena Navarro López says the experience is rewarding.

"I was sort of the black sheep by not riding before," Navarro says. "It has been hard to make the extra commitment to the team, but it is a sport we all like and is so beautiful."

The discipline required to remain in lockstep with her horse and the others, she says, has built up her mental strength to the point of being able to take on even more responsibilities.

Strength—both physical and mental—shows up in spades in everyone who dons the traditional dress and dares to bring her horse to a sliding stop in the middle of the dusty arena. Any charra will tell you that, for every minute spent performing, hours have been spent training, grooming, and rehearsing.

What makes it all worth it, according to Pliego, is the reaction she gets from her family: "As you emerge from the dust, adrenaline pumping, and see how proud our families are and hear them cheer us on, yeah, that is it." ‡

Read More

AGRICULTURE, SPECIALTY/NICHE

A Taste of Place

Vasilos Gletsos' beer provides—literally—a taste of rural Vermont.

AGRICULTURE, SUSTAINABILITY

Produce on the Plains

Food crops thrive in corn and soybean country.