Agriculture, Specialty/Niche December 01, 2024

A Taste of Place

Vasilos Gletsos' beer provides—literally—a taste of rural Vermont.

by Steve Werblow

Winemakers use terroir to describe the effect of the environment on the taste of a wine. Wunderkammer beers are a complete expression of terroir, a celebration of the Vermont farms and forests where Vasilos Gletsos gathers ingredients like mushrooms, lichen, and goldenrod and brews them with local malt and hops into magic.

"It makes you feel like you're going for a walk in the woods," Gletsos says as he strolls up a rural lane outside of Albany, Vermont, towards the brewhouse he built in a former on-farm cheese creamery. "I've never had that experience drinking an IPA before. There should be, on the surface, enjoyment, a nice, pleasurable drinking experience. That's just the starting point. But having these more complex flavor profiles, adding a low level of acidity to beers gives them so much more dimension."

Wonderment. Gletsos, a printmaker and puppeteer, has lived all around the U.S. He says moving back to Vermont in 2015 taught him to relish the seasons, forage for wild foods, and—most important—take the time to enjoy his walks in the woods.

"It wasn't really until I got into foraging that I stopped to smell the roses or flip over the rock and see what's happening there," he says. "I love that sense of awe and mystery and wonderment that you get from really exploring the woods in a deep kind of way."

That awe is evident in the name Wunderkammer, a German term for a cabinet of curiosities. Wunderkammers became popular in the 1500s as world-savvy traders and explorers displayed their collections of natural and cultural objects. They were the precursors of modern museums, places for surprise, learning, and contemplation. That's his beer in a nutshell—a bottle of surprises, of delight, of mystery, a bottle that makes you think.

"Honestly, I don't want people to be drinking four or five of my beers in a row," he says. "One a night is perfect."

Foraging. A Wunderkammer beer can be full of surprises. One of Gletsos' early brews focused on the "three sisters" Native Americans have grown for millennia: companion plantings of corn, beans, and squash. Others contain wild foods he finds on foraging walks.

"Foraging isn't like finding some golden-statue mushroom in the middle of the woods," he notes. "It's more like stuff that you can easily see on the sides of any pasture or woods, things like spruce tips, yarrow, sumac, or goldenrod, plants you can see when you're driving by."

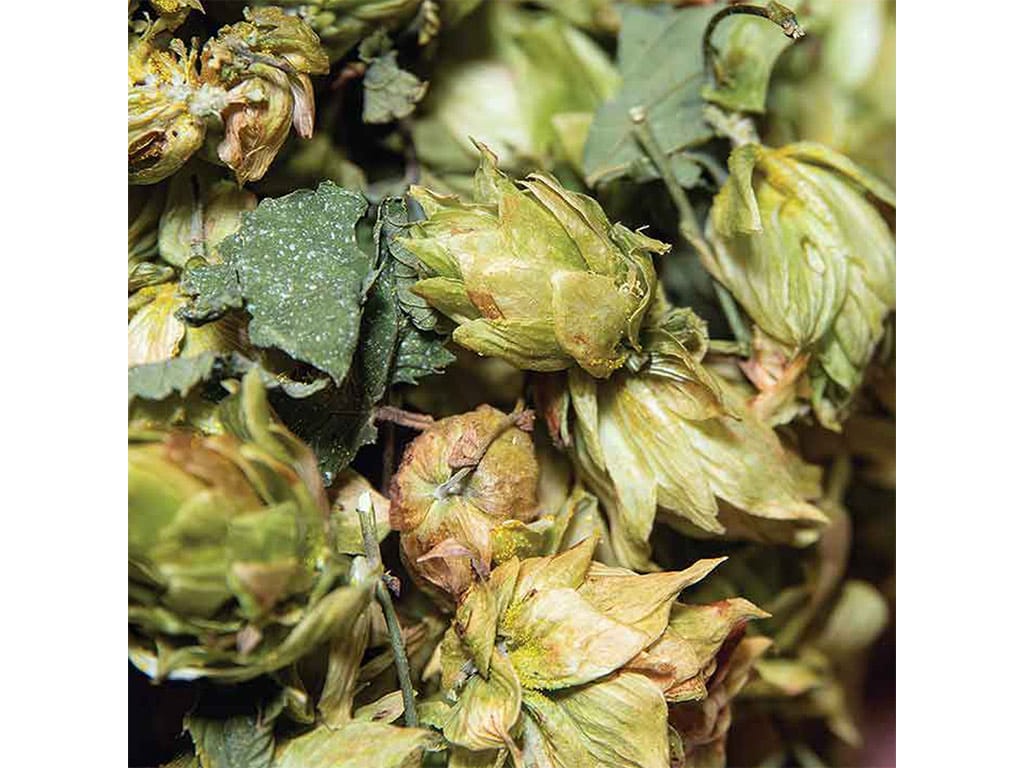

He purchases more traditional ingredients like Vermont hops and malted barley grown as close as possible by the small handful of farmers in New England or upstate New York who still grow barley.

"I try and get as local as I can," Gletsos explains. "It's definitely not cheaper, and it's not quite as consistent as commodity malt is, but I feel it's pretty high quality. And for the types of beer I make, it's got a good breadth of character."

The old dairy farm where Gletsos has sited his brewery provides plenty of foraging opportunities. It also links his brewing process to the local environment. Inside the former creamery, Gletsos heats spring water and malted barley in a stainless steel mash tun to release the sugars and flavors from the sprouted grain. While that's underway, he goes outside to build a fire in the brick box he built under a five-foot-tall copper kettle, preheating the 275-gallon vessel.

After as many as 2.5 hours, he separates out the spent grains to feed to his pigs or share with his landlord's sheep.

He pumps the rich, sweet runnings from the mash outside into the kettle over the fire and stokes the flame with waste wood from a local sawyer. Even the fuel is local. At very specific times during the boil, Gletsos adds hops and whatever other ingredients inspire him.

In the winter, Gletsos lets the boiled wort cool down naturally in the frosty nights. In the hot, humid summers, he uses a heat exchanger flowing with cold water to do the job.

The next step is loading up a food-grade plastic fruit harvest tote with the cooled solution, which is called wort. He trundles the wort a few hundred yards down the road to an igloo-shaped, underground concrete haven that was designed to be the farm's cheese aging cave. Its thermal stability makes it just as great for aging beer as it was for aging cheese.

There, he adds a combination of yeasts and bacteria—chosen for the levels of sourness or acidity he's aiming for. The process is called "mixed culture," and results in much more complex flavors than a single yeast strain can produce.

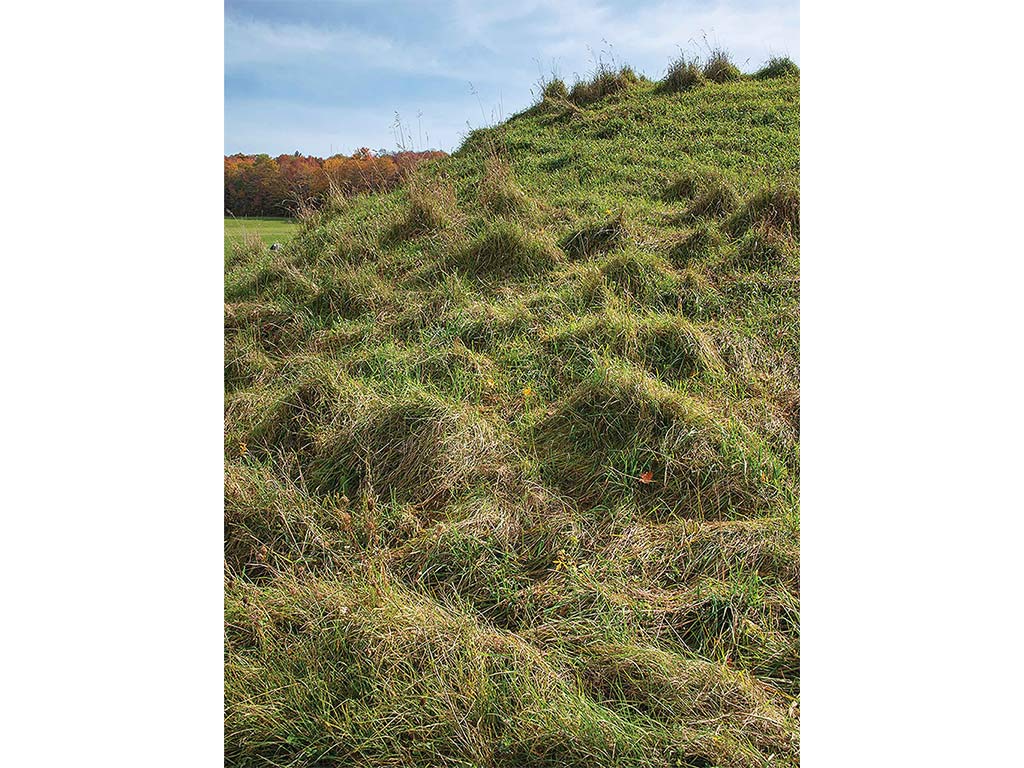

Above. Beneath the mound on this Vermont dairy farm is a former cheese cave that serves as the aging room for Wunderkammer beer. Whole hops from Vermont fit Gletsos' brew-local ethic. This scenic dairy farmhouses Gletsos' Wunderkammer Biermanufaktur, the brewery driven by Vermont's fields and forests, as well as its changing seasons. Arcas is a rich, mixed-culture farmhouse ale. Wunderkammer beers age in oak barrels. In the background is a drawing of a winged Death's head Gletsos drew with charred bits of wood. He based the drawing on a classic Puritan tombstone carving, and says it's contemplative.

Adventure. Along the way, other wild yeast and bacteria can join the mix. It's another expression of terroir, for sure. It also means each batch is its own adventure.

"I'm recognizing that the whole process that I've built here is an equal participant," he says. "You have to approach the beer, at every point, like a new beer. You have to see where it's at, no matter what sorts of aspirations you've had for that beer, whatever your designs for it. Sometimes it's exactly the same as what happened before, but sometimes you have to recognize what it is you've developed. Recognizing that and seeing what it's contributing is just as important as whatever intentions you started with."

After the wort is fully fermented into beer, the adventure continues.

Gletsos ages his beers in oak barrels like winemakers and whiskey producers do. In the barrel, bacteria metabolize wood sugars, the brew is aerated gently through the permeable wood, and flavors of oak leach into the beer. This is where the beer matures.

After aging, Gletsos bottles his beer with a pinch of yeast and sugar to create a secondary fermentation that lightly carbonates the final product.

In all, Wunderkammer produces about 200 barrels per year, or about 6,200 gallons. That's about the output of a single week at the Portland brewery where he used to work, or a small portion of what he used to produce as head brewer at nearby Hill Farmstead Brewery, where Wunderkammer began as Gletsos' side project.

Small audience. Gletsos isn't out to conquer the supermarket shelves with Wunderkammer beer. At beer festivals, in direct sales from his storage facility, through the distribution company he established, and with his bottle club, he's looking to provide dedicated fans with a beer adventure.

He's giving them a very special taste of a very special place. "It doesn't have to be for everybody," Gletsos says. "I'm making a very small, niche product for folks who really get excited by the uniqueness, the experimentation, the variation.

"It's like from my puppet theater background: you gather a small audience around you." ‡

Read More

AGRICULTURE, EDUCATION

Farming Today's Alaska

Boom or bust, there's no cooling the pioneering optimism of Alaskan producers.

SPECIALTY/NICHE

A Sport of Beauty

Grace, athleticism...and a cloud of dust.