Agriculture, Livestock/Poultry January 01, 2024

Meat Straight From the Farm

.

USDA-inspected on-farm slaughter meets quality and economic goals.

Everything about Jon and Robin McConaughy's Double Brook Farm on-farm meat processing operation defies conventional wisdom. They went super-local in the face of meatpacker consolidation. They went multi-species in an era of specialization. And their quiet little slaughterhouse is situated a stone's throw from million-dollar homes in the suburban Hopewell Valley near Princeton, New Jersey.

The McConaughys started raising animals in 2004 to teach their children where their food came from, and got into processing because of their interest in animal welfare and meat quality.

"We consider slaughter to be one of the most important things we do," says Robin. "You raise these animals in their natural environments. They're eating a diet that's more natural for them. They're living in family groups for the most part. They're led from the field to the slaughterhouse by a farmer they know. To have the last part of the process be chaotic or scary for them in any way would defeat the purpose."

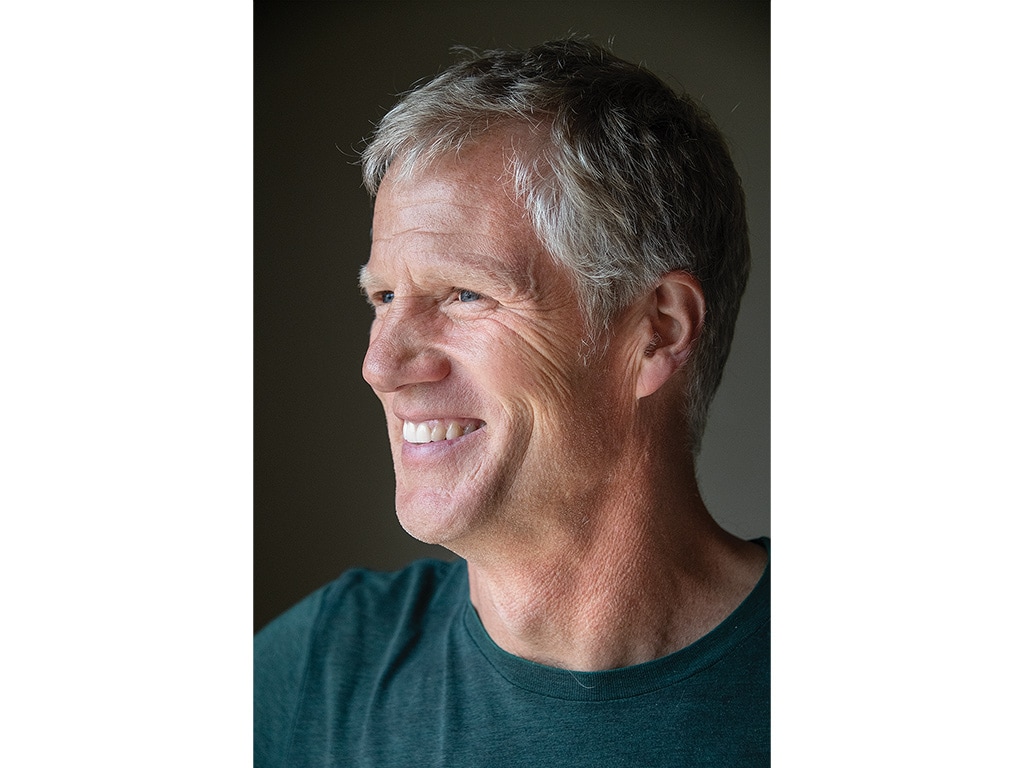

Above. Devon cattle share 800 acres of New Jersey pasture with sheep, goats, pigs, chickens, turkeys, and ducks. Most states allow on-farm processing. Before farming, Jon McConaughy worked on Wall Street; Robin was a corporate headhunter. The McConaughys set their meat prices in step with supermarkets, not gourmet shops. In-house processing, minimal transport, and close connections with retail make it possible, says Jon.

Numbers. In a typical week, the Double Brook Farm team processes eight pigs, five to seven sheep, two steers, and one calf for rosé veal, says Jon, as well as a complement of chickens, turkeys, and sometimes goats or ducks to meet demand. All meat is USDA inspected, which allows the McConaughys to sell their meat at the meat counter and casual restaurant of the Brick Farm Market and on the menu of the Brick Farm Tavern that they launched in Hopewell, NJ.

Last year, the couple transferred the market café and tavern to Otto and Maria Zizak, chefs who left their acclaimed Brooklyn restaurant for the chance to connect with a local, nose-to-tail supply of great meat and produce.

Chefs—or markets—that can utilize entire animals are key to success for on-farm processing, note the McConaughys. Interest in healthy pet foods has been a huge boon, as has the Zizaks' skill in preparing classic rural European dishes that utilize less-popular cuts of meat. Burgers and rustic-style dishes also can be priced to attract diners all week long, not just for pricey Friday and Saturday night dinners.

"It's not as far off-center as you would think," says Jon. "It's just that the average chef doesn't have the incentive to do it."

Zoning. The McConaughys said working with local officials wasn't a problem when their vision shifted from building a commercial slaughterhouse—which would have required a zoning change and public hearing—to realizing that they were building a facility covered under laws that allow farmers to process their products on-farm. That allowed the couple to focus on outfitting the barn-like structure with the cleanable surfaces, office, and bathroom space required by USDA and securing construction permits from the municipality.

In all, the facility cost about $500,000 to build in 2015 and takes about $125,000 per year to operate. Jon calculated a three-year payoff compared to the time and expense the Double Brook team used to spend driving animals to a commercial slaughterhouse and paying for processing.

True to form, the McConaughys' advice to other livestock producers veers from the expected.

"Capacity utilization is what they pound into us at business school, but the reality is the capacity utilization we're talking about is the time of the farmer rather than the equipment, because equipment that used to be super-expensive is now fairly cheap," Jon says. "So the technology has gotten us to a point where it doesn't make sense in terms of on-farm processing to have the machinery busy all the time. Rather than have a central slaughterhouse, it makes more sense to have a central butcher. So on Monday, the person can be on one farm and on Tuesday another farm, so the butcher is the one driving around, not truckloads of animals."

Since establishing their slaughterhouse, the McConaughys have helped others develop processing strategies to achieve economic and environmental goals.

"Interestingly enough with a lot of the sustainable stuff," Jon points out, "if you try to fix one problem, you fix a bunch." ‡

Read More

AGRICULTURE, LIVESTOCK/POULTRY

Sale Day in Mankato

A small town's sale barn is a boon to this county.

AGRICULTURE, SPECIALTY/NICHE

Eat. Shop. Stay.

Norfolk County, Ontario farms band together to build an ag tourism draw.