Agriculture, Sustainability November 01, 2024

A Miracle in Plastic

Spanish greenhouse cluster is a hotbed of innovation and sustainability.

by Steve Werblow

The greenhouses of the Spanish province of Almería are visible from space: 82,656 acres of vegetables and fruits under a sea of protective plastic, a bright flash along the olive-colored Mediterranean coast. All that plastic might sound like an environmental catastrophe unrolling in slow motion. But beneath those acres of sheeting—all of which will be recycled at the end of its useful life—is one of the world's biggest integrated pest management success stories. It's a model of an industry uniting to make huge strides in sustainable farming and put top-quality produce on Europe's tables.

It started as a disaster. In December 2006, German authorities found traces of isofenphos-methyl, a '70s-era insecticide, in sweet peppers grown in Almería. Thrips and whiteflies had become resistant to the shrinking arsenal of insecticides, and desperate growers turned to an off-label tool. Other importing nations found residues, too, and major buyers in the European Union and Russia closed their doors to Almería peppers.

"Chemical control had come to a dead end,” says researcher Jan van der Blom at COEXPHAL, the Association of Fruit and Vegetable Growers of Almería. That was an almost instant catastrophe for Almería's 14,000 growers, who represent about 60% of Spain's greenhouse production and depend on export markets for at least half of their sales.

Humble beginnings. Spain's greenhouse hub was built carefully and deliberately in a most unlikely place. Almería was among the poorest of Spain's 50 provinces, its dusty landscape favored by film crews as a stand-in for the deserts of the American West in Clint Eastwood's classic drifter movies, or for the blowing North African sands in films like Lawrence of Arabia and Patton.

But under that sand is a rich aquifer replenished by mountain snowmelt, and people and plants on the surface enjoy an average of 3,000 hours of sunshine—320 sunny days—per year.

In the 1960s, villages started popping up in Almería. Farmers from inland regions moved to the coast and began literally building new soil by adding 16 inches of rich topsoil and 2 inches of manure, topped with a coat of sand to minimize evaporation. Infrastructure was built just as deliberately, with Cajamar Caja Rural—a cooperative bank—setting down roots in the regional center of El Ejido to finance development. Within a decade, Cajamar also opened an experiment station, Las Palmerillas, to help drive innovation and return on all the investment that was pouring into Almería.

At 3.71 million metric tons of tomatoes, sweet peppers, squash, melons, eggplants, and green beans in 2022/2023, Almería's greenhouse output is equal to all of Germany's indoor production. It's also efficient, requiring 22 times less energy than indoor growing operations in central Europe and yielding 12 times more food per unit of water than other production methods.

Above. Chrysopa (lacewings) like this one at the Cajamar Las Palmerillas Research Center are fierce aphid killers. Packets of predator mites. Almería's greenhouse industry unites through umbrella association HORTIESPAÑA and its member organizations. Cajamar researcher Lola Buendía scouts for beneficials.

IPM expertise. In a way, there were few places on Earth better-positioned to pivot to IPM than Almería. By the time the pepper scandal blasted into the headlines in 2006, Almería was already a global hub of expertise in raising natural predators and parasites for pest control. Many local growers were also gaining experience with IPM in their tomatoes.

Bumblebees had gained a strong presence in greenhouse tomatoes as a highly effective pollinator, explains van der Blom. To protect the bees, growers in the tomato portion of their rotation minimized insecticide applications and experimented with releases of beneficial insects, building confidence in IPM.

Van der Blom says biocontrol acreage was relatively small in the 2006/2007 season–about 1,275 acres—but by 2010/2011, biocontrol was used on 49,600 acres. That included 92% of the province's pepper acreage. Today, more than 15 years later, 100% of Almería's peppers, 80% of its eggplant, and more than half of its tomatoes are managed with biocontrol, and 65% of the province's cucumber pest control programs start with beneficial insects, van der Blom points out.

Today, companies like Almería-based Agrobio sustain the IPM efforts by breeding billions of parasitic wasps, predatory mites and bugs, and syrphid flies. Agrobio produced enough beneficials and bumblebees last year to treat more than 111,000 acres worldwide.

David Beltran, who leads the production of mirids at Agrobio, adds that his colleagues have also become experts at breeding prey species to feed the beneficials. Wheat bran sustains the cereal mites, which nourish the fast-growing beneficials that end up distributed in boxes or little pouches.

Meanwhile, growers plant "banker plants" along the edges of their greenhouses inside and out to attract and sustain beneficials. In a house full of tomatoes, that might include a mix of nectar-rich flowers. In watermelons, it's likely to be thick stands of cereal grain in the row middles to draw in prey species. There's even a smartphone app to help growers choose the best banker plants for their needs.

Collective effort. Almería's IPM revolution was not waged one 6.25-acre farm at a time. The Spanish and Almería governments poured money into incentives to help pay for biocontrol organisms and training for pest control advisors. But policymakers recognized that isolated patches of IPM-managed greenhouses could be flooded by pests from poorly managed neighbors. For IPM to work, it needed to be applied across the landscape. So to qualify for the incentive payments or subsidized visits from pest control advisors, farmers needed to belong to an association or group.

In all, 77 grower associations were formed or strengthened to allow growers to participate in the incentive programs. And though the 2008 financial crisis slashed the subsidies by 70 to 80%, notes Miguel Acebedo of the Almería government—a co-author of a case study in the journal Agronomy—local farmers stuck with biological control. Why? Because it worked.

In fact, Acebedo and his co-authors note, the cost of pest control in Almería fell by 32.16% between 2007/2008 and 2012/2013, which they attribute to shrinking pest pressure. In 2007/2008, thrips were present in 30% of the monitored pepper plants in Almería, 10% of the plants were infected by tomato spotted wilt virus, and up to 9% of the fruit showed the effects of the pest. Three crop seasons later, those values had dropped to 17.3%, 0.9%, and 1.1%.

Success begat success, notes van der Blom. When Tuta absoluta—the South American tomato leafminer—appeared in Almería in 2009, natural populations of a local parasitic wasp boomed and brought the pest under control. Van der Blom says IPM practices in the greenhouses allowed the wasps to thrive...and save the day.

Premium product. Almería's collaborative spirit lives on in cooperatives like La Palma, which counts 750 growers as members who produce 70 million metric tons of vegetables and fruit per year. Of that, 80% are tomatoes.

The co-op sells hard on the superior taste of its varieties—the product of a vigorous in-house development program, 220 taste testers, and state-of-the-art laboratories to track brix, nutrients, and other components. Customers also appreciate the fact that 100% of La Palma's growers practice IPM, that the co-op promises traceability of its produce, and that La Palma has pledged to achieve zero-waste by 2025.

Co-op agronomists visit each La Palma grower at least once every 10 days, says sales manager Juan Vicente Gallego. That's important for reaching ecological goals as well as quality goals that maintain La Palma's premium position.

"The better you treat the crop, the better it will taste," he says.

Recycling. Almería's greenhouse industry produces about 30,000 metric tons of plastic waste per year, notes van der Blom, but 80% of that—including 100% of the greenhouse cover material—is recycled. In fact, concentrating all that high-value plastic in one place makes recycling economically attractive, he adds. Most of the final 20% is burned for energy.

The challenge now is to catch consumers up on the positive story taking place under all that plastic. Juan Carlos Pérez-Mesa of the University of Almería says 34% of European consumers think Spain's greenhouse industry has a negative environmental impact.

Van der Blom says Almería is living proof of the powerful—and compelling—advantages of IPM.

"We're showing that the green view is possible," he says. "We are showing this is not fantasy." ‡

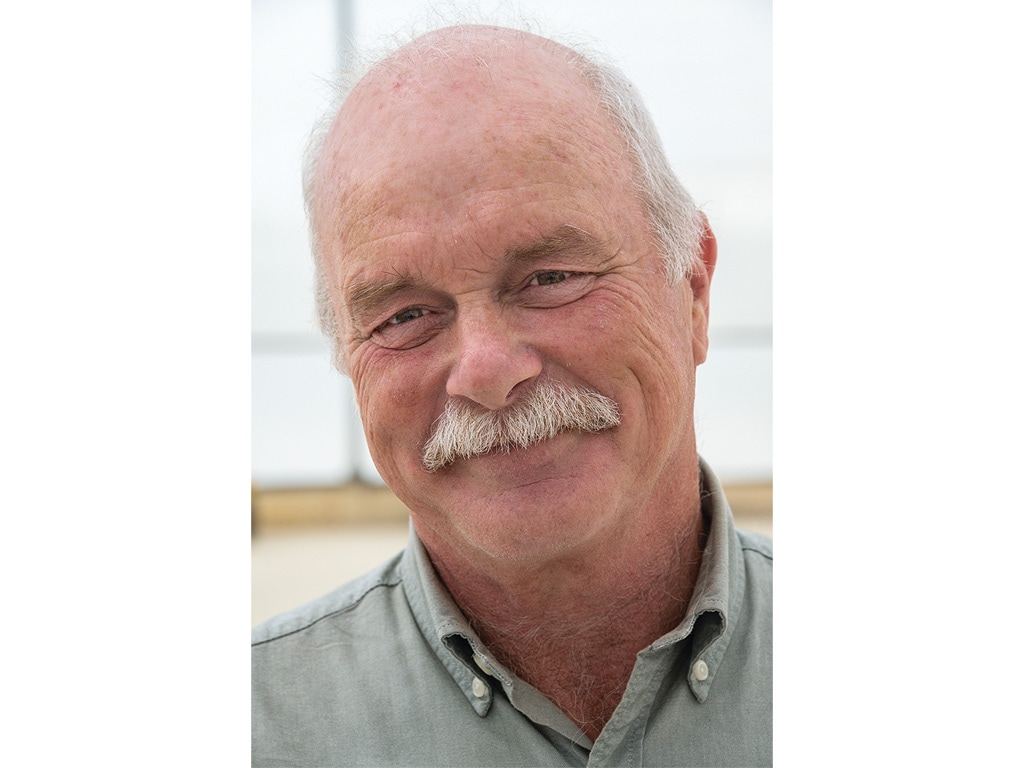

Above. Jan van der Blom of Fruit and Vegetable Growers of Almería says integrated pest management was widely adopted in just a few short years in Almería. Almería is a major source for Europe's winter tomatoes, peppers, melons and more. "Banker crops" at left nurture beneficials. The "sea of plastic" laps at the edges of downtown Motril. Agricultural engineer Monica González is a diversity specialist for Agrobio, creating environments in greenhouses to encourage beneficial insects to thrive. La Palma co-op staked out a premium market for tasty fruit.

Read More

AGRICULTURE, SUSTAINABILITY

Hardening Our Arteries

Disaster-proofing our major transportation corridors.

AGRICULTURE, SUSTAINABILITY

Farmers Fueling the Future Part 2: Conservation Legacy

Innovation legacy powers Kansas farm.