Agriculture, Farm Operation November 01, 2024

Prevailing with Pintos

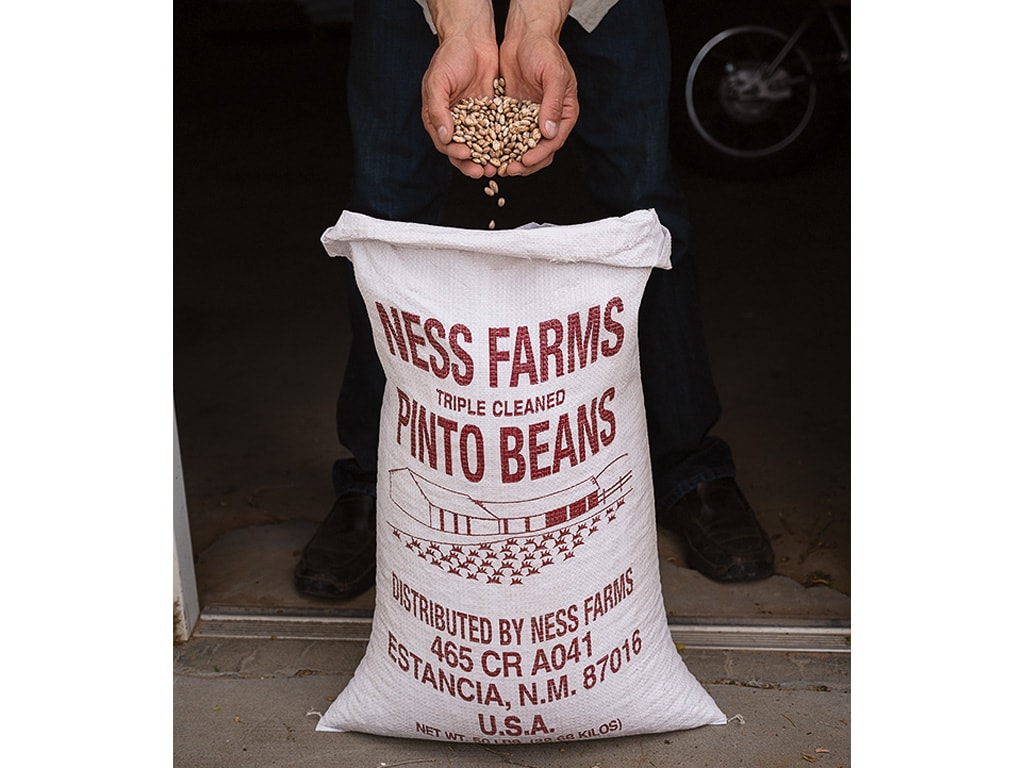

Branding a commodity keeps beans in the rotation.

by Martha Mintz

The Estancia Valley in central New Mexico is fairly flat, but the rise and fall of the agricultural industry in the region has been quite the roller coaster.

The Ness family was sick of going along for the ride that trended down more often than up. Seizing control, they built their own track with Ness Farm branded pinto beans. This ride has them climbing to a better farm future.

Persistence. Steven Ness is a farmer. Always has been. Always will be. "I've never done anything else. It's all I know, and all I want to do," he says.

Ness started farming with his father while still in high school. They raised pinto beans and dairy hay continuing generations of tradition. Tradition Ness realized was in jeopardy as he gradually took over farm management. Margins were razor thin.

His father and brother had partnered in a car dealership. It loomed in Ness' peripheral as he considered his path forward in farming.

"I absolutely didn't want to go sell cars part-time, so I had to figure something else out," he says. He shifted focus to marketing, tapping into the momentum of the local food and farm-to-table movements for a farm boost.

Classic revamp. The Estancia Valley was once dominated by pinto bean fields. Mountainair was once home to the nation's largest pinto bean processing center, earning the title of ‘Pinto Bean Capital Of The World.'

According to the town's website, at its peak the facility filled 750 rail cars per season from 40,000 acres of production. Area pintos were used as the main ration for American soldiers during World War II. Ten years of drought essentially killed the industry.

"There are only a couple of us growing pintos now," Ness says.

Local processing infrastructure was long gone, making commodity pintos a rapidly losing battle. Ness saw opportunity to capitalize on the lingering regional reputation for pintos to build local direct markets.

Above. Online engagement lets Ness Farm customers tag along virtually in the field. YouTube videos, a web site and social media serve as forums for announcements, answering questions, and setting expectations. For instance explaining how muddy harvest conditions might impact the look of the fresh, white pintos customers anticipate in fall.

After testing the waters using a local on-farm cleaner and wholesaling with generic packaging, Ness was encouraged to commit.

His uncle, Patrick Ness, scratched out a simple farm logo for the Ness Farm Pinto Bean branded bags.

The farm sits within an hour of Santa Fe and Albuquerque where they got on the shelves of a few market-style stores. Demand grew.

"People kept calling asking for more. I realized this was the direction we needed to go," Ness says.

He purchased a building in nearby Moriarty once used as a potato shed—another regional crop that boomed and busted. By 2012, Ness and his dad had their own cleaner and packer on line.

A decade later, brand recognition has continued to grow. Pinto beans are holding steady as a profitable crop for Ness while other crops have faltered. The dairies are gone, tanking the local hay market. Irrigation water is expensive and increasingly uncertain. Ness continues to pivot.

In the field, stacking rotations brings multiple income opportunities. After harvesting pintos Ness seeds triticale which is leased for winter grazing. Once cattle are pulled, the crop is watered, fertilized, and makes hay by June. Then it's right back to pintos.

"We're essentially getting three crops, which is unheard of here," Ness says. He's also pushing pinto marketing with the future in mind.

They've diversified packaging, offering 2, 5, 10, and 25-pound bags and restaurant wholesale.

Stewarding the customer connection is a critical component.

"They need to connect the brand with a family farm," Ness says. In the past, that has meant giving tours to customers that followed GPS to the farm thinking it was a store. That's not feasible at scale, so Ness started the Ness Farms YouTube channel.

He shares 'Day in the Life' content like field work, weather, wildlife sightings, downtime activities, even pinto cooking videos featuring his mom Sandy. His wife Tobie runs the farm's social media.

Their kids, Daniel (12) and Ilana (9), help film and edit the videos. Ness hopes their efforts will help provide both a farm future. Ness thinks the outlook is good.

"We've created a system where we set a price to cover costs and make a profit. And people will always need to eat," he says. ‡

Read More

AGRICULTURE, FARM OPERATION

Going Against the Grain

First generation farmer finds footing with sod.

Agriculture, Livestock/Poultry

Non-Profit, Plenty of Benefits

Non-profit creamery is a lifeline for isolated dairies.