Costumes, smiles, and strong arms are the order of the day at the annual West Coast Giant Pumpkin Regatta in downtown Tualatin, Oregon. The 20-year tradition draws thousands of spectators—and thousands of pounds of giant pumpkins. Members of Pacific Giant Vegetable Growers grow the fruit and conduct a weigh-off the day before.

Specialty/Niche September 01, 2024

The Battleship "Pumpkin"

Grow the pumpkins. Row the pumpkins.

by Steve Werblow

You know how a kayak cuts the water like a knife, silently slicing through the surface of a pond? Well, paddling a 1,400-pound pumpkin is not at all like that. It's more like trying to row a fruit-flavored bumper car across a lake.

At least that was the scene at the West Coast Giant Pumpkin Regatta at Lake of the Commons in downtown Tualatin, Oregon. Since 2004, competitors have raced around the waist-deep water feature in carved cucurbits. It's the ultimate Halloween naval battle, combining pumpkins, costumes, and all-ages fun with a fascinating horticulture lesson.

For one thing, the regatta pumpkins are not your average pie fillers, or even front-porch jack o'lanterns, which represent the Cucurbita pepo species. The Great Pumpkin Commonwealth—the rulemakers and cheering squad behind giant vegetable growing— classifies C. pepo as field pumpkins and marrow squash.

The jaw-dropping, scale-straining fruit are the C. maxima species. C. maxima fruit have bigger cells, higher water content, and a longer period of cell division than C. pepo. Another crucial difference: giant pumpkins lack the genes that signal regular pumpkins to stop growing.

Speeding up. The quest for a great pumpkin is nothing new. The Bradshaw and Sons seed catalog dates its "Mammoth" variety of pumpkin seed back to 1834. Naturalist Henry David Thoreau wrote about the 123-pound pumpkin he grew in 1857. William Warnock of Ontario, Canada, displayed a 365-pounder at the 1893 Chicago World's Fair and a 400-pounder in Paris in 1900.

In 1904, Warnock beat his own best with a 403-pound pumpkin. Remarkably, Warnock's record then stood for more than 70 years.

Another Canadian, Howard Dill of Nova Scotia, launched the modern pumpkin filling-the-space race in 1954 with a cross he called Dill's Atlantic Giant. In 1980, Dill broke Warnock's longstanding record with a 459-pound pumpkin, and things went into overdrive.

By 1996, Nathan and Paula Zerr broke the 1,000-pound barrier. Six years later, Ron Wallace was first to cross the 1-ton mark with a 2,009-pound monster. Last year, a horticulture teacher named Travis Gienger hauled a world-record 2,749-pounder from his home in Anoka, Minnesota, to a weigh-off in Half Moon Bay, California.

Giant pumpkins aren't just a North American fascination, either. The three record pumpkins prior to Gienger's were grown in Italy, Belgium, and Switzerland.

Weigh-off. Dai Hashimoto of Awaji Island, Japan, earned a ticket to the 2023 Oregon regatta when his 1,114.9-pound pumpkin topped Japan's contest. Sporting pumpkin-orange hair, Hashimoto was on-hand in Tualatin on October 21, 2023, as a line of pickup trucks and trailers rolled into the parking lot of Stickmen Brewing Co., groaning under the weight of massive pumpkins ready to claim their ranks in the Pacific Giant Vegetable Growers' annual Terminator weigh-off.

First-time entrant Susan Ashenfelter of Banks, Oregon, watched a forklift gently lift her season's work. Getting it into the truck took some help, she notes, but her day job as a nurse lifting heavy patients helped her perfect her hoisting technique.

Ashenfelter says she was inspired to grow the pumpkin in her new garden after she wasn't chosen in the annual lottery for guest rowers at an earlier regatta.

"I was so disappointed I told my husband, 'I'm going to make my own,'" she says. "It's just goofy enough that it hits all my buttons."

Next to her, Liesl Wollman of Beaverton, Oregon, stood next to a pallet holding her Atlantic Giant pumpkin and marrow gourd, big products of a long summer.

"People say, 'You're so tan! Did you go somewhere?' No, it's pumpkin season!" Wollman laughs.

Shane and Jennifer Bridges of Sherwood, Oregon, grew their inaugural entry on the farm they dedicated as a haven for children battling cancer and their families. At Embrace Compassion, says Jen, "we throw a festival once a month, 7 months a year—they come and watch the pumpkins grow. We can't take cancer away, but we can bring joy with pumpkins. Pumpkins bring a lot of joy."

They can also bring a bit of frustration, notes Ron Edwards of Dallas, Oregon, who spends the growing season shading his pumpkins and carefully monitoring water and fertilizer to ensure they don't grow too fast and burst.

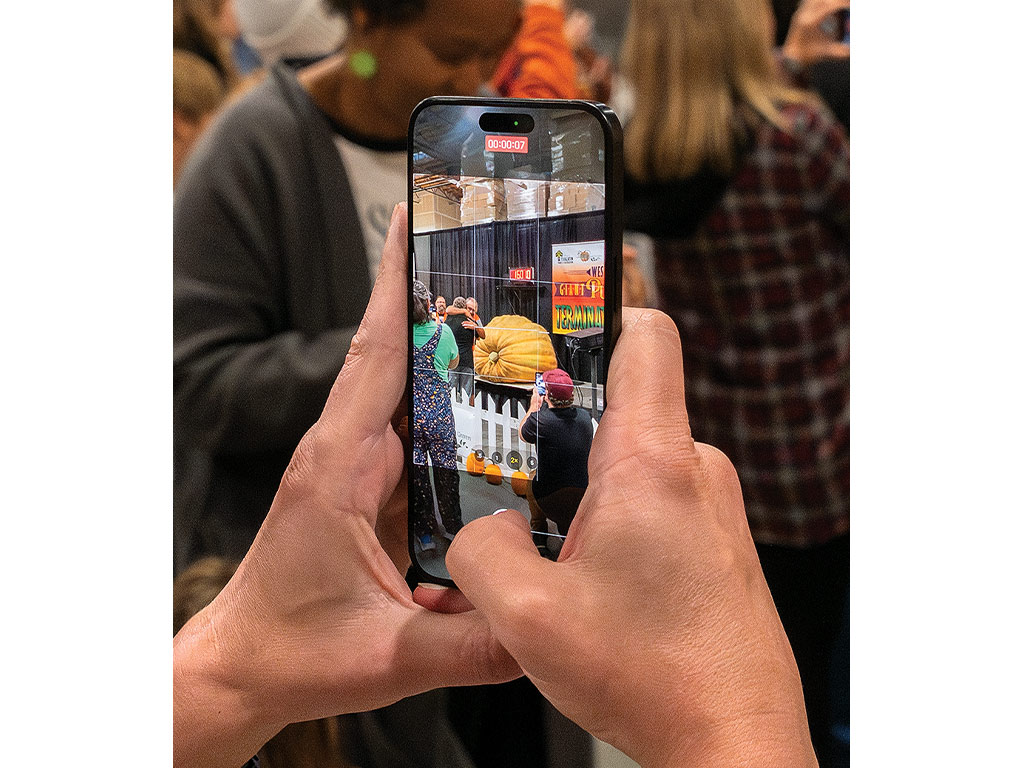

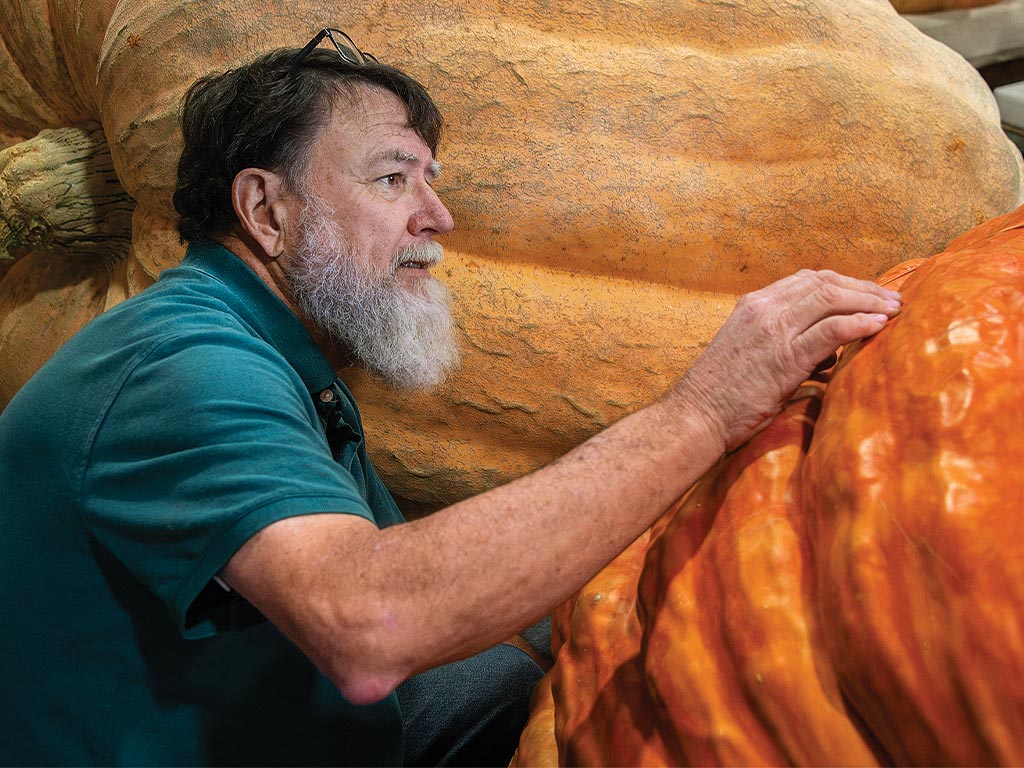

Above. A big lineup at the Pacific Giant Vegetable Growers' weigh-off in Tualatin last year. It takes a lot to haul a half-ton fruit. Oregon chapter president Kendall Spielman has been growing for 10 years. Capturing a moment at the weigh-off. This pumpkin was too big in circumference for a 16-foot tape measure. Susan Ashenfelter rests on her entry. Matt Sekreta shows off his 103.5-inch gourd. Grower Bob Cohen inspects a pumpkin for cracks. Ron Barker celebrates on the 1,600-pound pumpkin that helped him earn a Master Gardener jacket.

Babysitting. "It's 6 months of babysitting," Edwards explains. "You've got to keep the surfaces soft and pliable. If the sun beats down on it, it gets hard and cracks. A lot of times around Labor Day, they'll blow up. It's frustrating."

Edwards scrutinizes his soil tests, supplementing the soil with mycorrhize, fungi whose filaments channel nutrients and chemicals between plants and soil. There's sea kelp from Maine with its load of micronutrients, humic acid to boost soil microbes, and 12 yards of compost per year.

Jim Sherwood of Mulino, Oregon, endorses the soil-centric strategy. "Pay attention to your soil," advises the long-time grower. "Let your soil do most of the work."

Of course, growers do plenty of work, too. Many hand-pollinate their flowers, carefully managing genetics. They prune away excess fruit and vegetation that doesn't contribute to their chosen pumpkins. They pluck off insects, fight diseases, and leave enough slack in their vines to permit the plant to accommodate a fruit the size of a golf cart under them.

For Matt Sekreta of Phoenix, Oregon, who has a passion for long gourds, champion fruit is all about ups and downs. He lets one or two long gourd vines climb the wire fencing inside the 14-foot wooden towers he built as growing chambers, then trains a fruit or 2 to grow straight down.

"The fruit starts growing an inch a day, then 2 inches a day," Sekreta says. "All of a sudden, it's growing 8 or 9 inches a day. During the first part of that growth, you want to start putting the gas on, feeding it with micronutrients and fungi. It's kind of like jet fuel."

This year, Sekreta is vying for the coveted orange Master Gardener jacket, recognition from the Great Pumpkin Commonwealth for excellence in 5 different species in a single season.

Celebrating big fruit and big achievements in the tight-knit community of giant vegetable growers is a victory in itself.

"The pumpkin plant is the journey," muses judge Maurizio Camparmo of Canada. "The destination is the friends you make."

Enter Sandman. Back at the 2023 weigh-off, the crowd cheered Jack LaRue's 10.46-pound tomato, Sekreta's 103.5-inch long gourd and the one from Brian Williams that beat it by 2 feet, and more.

Then...the main event. Pumpkins were forklifted to the scales to a booming soundtrack of Metallica, AC/DC, and Mötley Crüe.

Susan Ashenfelter's pumpkin hit solidly in the middle of the pack at 712 pounds, and she beamed like she won the Powerball. Jen Bridges videoconferenced the scene when her Embrace Compassion pumpkin rolled over 1,100 pounds, celebrating long-distance with the families that had helped it grow.

The crowd buzzed with anticipation as Jim Sherwood's monster swung over the scale, the last and biggest of the competition, a contender to tip over the 1-ton mark.

Shouts, cheers, and words of consolation rang out in equal measure as the scale's display read 1,997.5 pounds. It was a stinging disappointment—about 1 quart of water weight short of the goal. The crowd felt Sherwood's disappointment, but also shared the delight of seeing his mountain of a pumpkin that weighed as much as a 1970s Datsun B210.

"It's a competition," Sekreta points out, "but we want to see everyone successful."

Paddle or pie. The next morning at dawn, 22 giant pumpkins formed an orange flotilla at Lake of the Commons. Growers waded into the water with saws and scoops to prepare their boats. They carefully saved the seeds to trade or sell (hardcore growers will pay tens and even hundreds of dollars for a champion seed).

Spectators crowded the banks of the lake as wave after wave of costumed rowers paddled for glory—first growers, then VIP guests, the Tualatin fire department and police, and lucky winners of the regatta lottery. Judging by the smiles, everybody won.

"It's like working at an ice cream store—you're just handing out joy to everyone," said grower Jon Sestak of Silverton, Oregon, as he scooped his pumpkin before the race. "You just can't look at a giant pumpkin and not smile." ‡

Above. Costumed contestants compete neck-and-neck. Tualatin crews launch the pumpkin fleet. Giant pumpkin rowing events spark delight around the U.S. and Canada. Thousands line the lake each year, some hoping for a chance to paddle. Volunteers ready rowers. Four-time race winner Gary Kristensen carves his craft. Giant vegetable growers carefully track genetics. Seed from a champion fruit can command hundreds of dollars. Ron Edwards tries to make $300 per pumpkin in prize money or sales of fruit or seeds to cover costs.

Read More

AGRICULTURE, SPECIALTY/NICHE

Drafting New Passions

Borrowed horses lead to a slow-lane shift.

AGRICULTURE, SUSTAINABILITY

Farmers Fueling the Future - Taking Corn Higher

Meeting the ground crew behind clean jet fuel.