Moths are most often thought of in terms of gray, flat, thumb-sized triangular forms. This tiny yarrow plume moth instead has a long narrow body with wings that form a 'T' when at rest. This gangly pollinator is just one of the hundreds of thousands of moth species thought to exist worldwide. Bee species estimates sit at just 20,000.

Agriculture, Education September 01, 2024

The Mighty Moth

Tiny lepidoptera may be bigger pollinators than once thought.

by Martha Mintz

The sun sets, dousing the sky in pink as Claudia Fife and her citizen science partner power up the UV light in their bucket trap. For the next few hours the blue glow will lure moths from their nightshift pollination work at the Montana Audubon Center in Billings.

When the sun rises again, volunteers for the Montana Moth Project (MMP) will pick through the jumble of a haul looking for novel species or those previously undocumented in the county or state.

Their work is part of a statewide effort to beef up the once sparsely populated Montana database of lepidopteran species. This data may be increasingly in demand as scientists look to expand their understanding of how lepidoptera interact with and influence plant communities.

"Bees and butterflies get all the public attention because they're out during the day and we're out during the day. We tend to focus on the things we can see," says Mat Seidensticker, founder and executive director of Northern Rockies Research & Educational Services (NRRES) and the MMP.

"We've recognized moths as pollinators, but work done in the last decade is indicating they may play a larger role in pollinator networks than once thought."

A study published in 2022 reported moths made up a third of pollinator species recorded visiting red clover growing in alpine grasslands in Switzerland. Prior to this study, moths received no credit for their pollination work on the valued forage crop.

While this work photographically documented moths visiting an agricultural crop, the more advanced science of DNA metabarcoding may help tease out just how much of the heavy lifting moths are doing as pollinators.

Filling the gap. DNA barcoding is a process of identifying species using the unique DNA 'fingerprint' each species carries in a specific region of their DNA. DNA metabarcoding is a process where multiple species can be identified from a single mixed sample.

Recently the process has become fast and affordable, sling shotting forward research in complex ecosystems. Seidensticker uses it to analyze pollen collected from MMP specimens.

"We've been able to link moth species with hundreds of native flowering plants," Seidensticker says. Samples taken from moths collected at the MPG Ranch site in Florence, Montana, also revealed alfalfa, sainfoin, and brassica pollen. Brassica pollen was found in abundance.

"You get a sense they like that family of plants. There's a lot of mustard and canola grown in north central Montana, we suspect moths might be doing quite a bit of pollinating in those crops," Seidensticker says.

A study out of Great Britain reports moths are more efficient pollinators than their day-shift counterparts. As the third largest order of insects, they also far outpace bees and butterflies in terms of population and diversity.

There are around 160,000 recorded species of moths worldwide with double or more thought to exist. The U.S. hosts at least 11,000 species. Montana was a notoriously under-mapped, but ecologically diverse area. Efforts by MMP contributors have boosted the official Montana roster north of 3,000 macro and micro moth species, including two new-to-science species.

MMP partnered with the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity at Colorado State University to curate and house a voucher collection of Montana moths.

"Montana was almost completely missing in the official records. Most of the data was photographic, not specimens," says Chuck Harp, collections director for the museum. Not anymore. He's since preserved thousands of Montana specimens from MMP.

Each species is also DNA barcoded to create a robust library of data for ecosystem research.

A lack of this data is what led Seidensticker to found the MMP. He was using DNA metabarcoding to analyze diets of the nocturnal birds. Moths were a dietary staple, but results weren't precise due to the limited number of DNA barcoded moth species in the reference database.

"Your results are only as good as your data," he says. So he set out to improve the dataset. Along the way he's attracted a passionate team of people dedicated to drawing under-appreciated moths into the light.

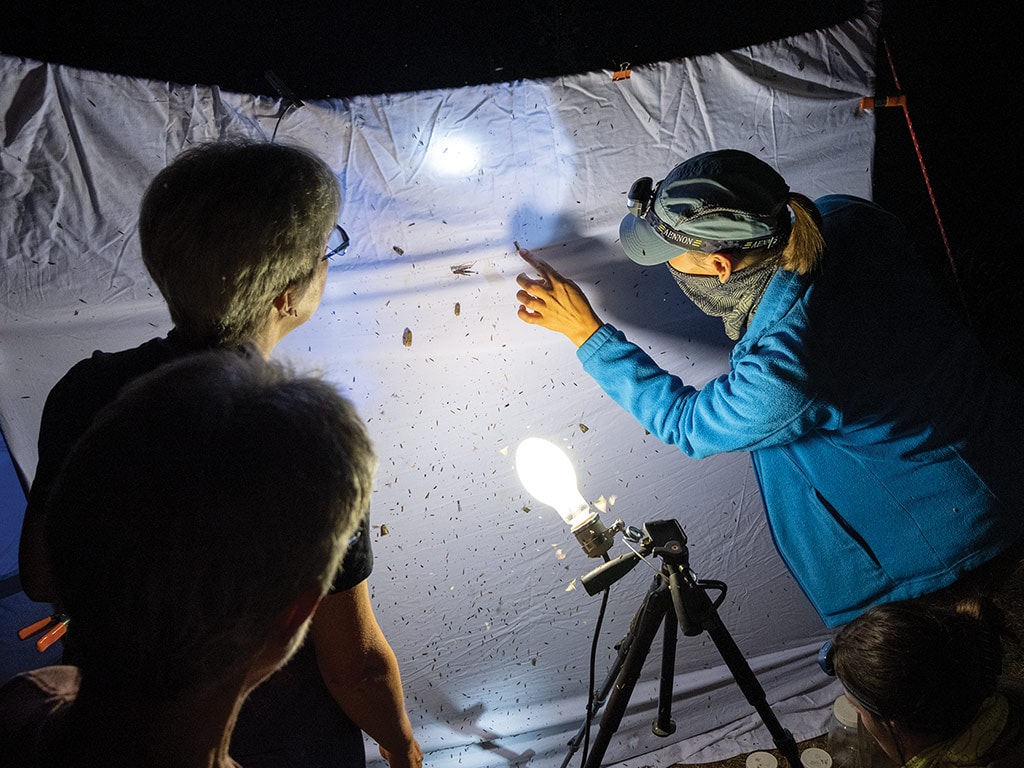

Above. The large size of the white-lined sphinx moth makes it easy to see the long proboscis moths use to dip deep into tubular-shaped blooms. Mat Seidensticker founded the Montana Moth Project to fill voids in the moth DNA record he needed for bird research. Its legion of smaller cousins, however, are the more prolific pollinators. Citizen scientists venture into the night to hunt for record species. Bucket traps yield the most results, but great fun is had hand-capturing moths drawn to lighted sheets. These chickweed geometer moths were submitted to the voucher collection. Immune to the fluttering onslaught, Marian Kirst helps volunteers ID moth species. Unique, even comical personalities are revealed upon close inspection, like this melancholy Catocala. Flashy or funny, citizen scientists Rebecca Mathias, Claudia Fife, and Mary Mullen collect them all guided by Kirst (far right).

The pink sheep. People tend to focus on the fraction of a fraction of moths that negatively impact agricultural crops, forests, or even the natural fibers of vintage clothing, says Marian Kirst, Billings-based entomologist and NRRES program development lead.

Those are the black sheep of the moth family. The large majority of species are an integral piece of a diverse landscape, serving as herbivores, pollinators, and prey. They're also often stunningly beautiful and interesting upon closer inspection.

There are moths with pink, blue, yellow, orange, black, and white color schemes. Tiny scaled wings feature stark geometric patterns or delicate floral hues. Grey overwings often veil underwings exhibiting shockingly vibrant colors.

"Io (EYE-oh) moths [of the giant silk moth family] feature deep blue eye spots with a tiny glint of white. It's like a beautiful pool of water on their hindwing. They're stunning," Kirst says.

Her posse of citizen scientists have come to appreciate the elegance and individual character of the different moth species. From the giant flashy members of the sphinx family to tiny plume moths.

"I used to just think of moths as things that fly in your face when you walk out the door at night," Fife says. After several years of mothing with the MMP, the avid gardener now pays them much closer attention. "When I see something flitting around I'm watching. Is it a Geometrid? Have I seen it before? It’s exciting."

Kirst lives for the excitement of the volunteers and is quick to point out the importance of their work. Fife and Mary Mullen are two of her most dedicated volunteers and have their names attached to several state records documenting expanded distributions of known species.

"It's wonderful to work with the volunteers and watch them take an interest in the world around them," Kirst says. Too often science is intimidating. "This work helps people see you don't need a PhD or fancy equipment to make significant scientific contributions, just a willingness to learn."

A bit of passion helps, too.

"It's exciting when you find something you haven't seen before," Mullen says. "The diversity of moths is fascinating. I was addicted from the start. I'm always taking pictures to show people how colorful moths can be."

Fife enjoys sharing her growing knowledge of moth species with her four-year-old grandson.

"He's a sponge for information. He'll see a moth and say, 'Oh Nana, is that a Catocala?'" Fife says.

Taking flight. An original goal of the Montana Moth Project was to collect moths in all 56 counties in the state. They've managed 52, establishing hundreds of state and county records.

The diverse landscape makes canvasing the entire state a worthwhile scientific endeavor.

"Montana is a special place for invertebrate species. There are so many types of habitats," Kirst says. They've collected high-altitude forests, prairies, sandhills, sagebrush steppe, even tundra and arid red desert.

The geographically unique Pryor Mountains delivered a new species, Protogygia pryorensis, that Kirst got to name.

The program attracted the annual Lepidopterists' Society meeting to Montana for the first time. Members attended from five countries, including a curator from the British Museum of Natural History. The meeting included a mothing excursion to the Beartooth Mountains.

"There was a lot of excitement about the work being done in Montana within the group," Harp says. "Many discussions were had about how to emulate this program in Wyoming, Idaho, Alberta, and elsewhere."

Beyond cataloging species, the MMP is also looking at how moths help shape landscapes.

Moths travel long distances, potentially helping promote genetic diversity in natural plant populations by transporting pollen. They also visit species that are more difficult for bees to access.

"Moths provide resiliency in the pollinator network and are a bio-indicator of environmental health," Seidensticker says. He's delighted to see the grassroots interest the Montana Moth Project has generated. ‡

Read More

AGRICULTURE, EDUCATION

How Weeds Are Changing

Some are developing resistance to herbicides they've never seen.

AGRICULTURE, SPECIALTY/NICHE

Drafting New Passions

Borrowed horses lead to a slow-lane shift.