Agriculture, Education September 01, 2024

Thousand-Year Timeline

Traditional Maya crops position this farm for the future.

by Steve Werblow

In the village of San Felipe in southern Belize, Juan Cho and his family keep their eyes firmly on the future by carrying on a tradition of sustainable farming that goes back thousands of years. Juan and his wife Abelina are part of the Maya community spread from southern Mexico through Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras.

From their 20 acres of lush forest, the Chos harvest food and medicinal crops. Many would be familiar to countless generations of their ancestors. Others were brought to Belize by former Confederate soldiers settling there after the U.S. Civil War.

Visitors to the Cho farm won't see the broad cornfields or rice paddies that are a familiar sight on Mennonite-run farms around Belize. Instead, it takes a few moments of peering at the wet, green leaves and the deep shadows for the farm to come into focus as an intricate puzzle, its pieces interlocked in time and space.

Towering cohune nut palms, gangly papaya trees, and sturdy breadfruit hang their crops high off the ground while providing shade for shorter plants. Trees bearing cinnamon, allspice, and frankincense-like copal form a middle story, surrounded by herbaceous crops like ginger, cardamom, chiles, and lemongrass.

The ground-level crops are short-term producers, quick to yield. Palms and woody plants are medium-term or long-term producers, Cho says. Squarely in the middle is cacao, which matures in 5 years and thrives in the shadow of a healthy rainforest.

Six months a year, the Chos harvest the greenish-yellow, football-shaped pods of cacao trees, an indigenous Maya variety called criollo known for its rich, mild flavor. Their traditional cultivation practices qualify the Chos for organic certification, which would add about 20% to 30% to the value of the family's beans if they sold them through the Toledo District's cacao cooperative to global markets.

Instead, the Chos process their beans, 150 pounds at a time, into Ixcacao chocolate (ixcacaomayabelizeanchocolate.com). Sales of their chocolate in Belizean shops and to guests who visit for farm tours, tastings, and Abelina's cooking have made the Chos an economic engine, buying local meat and produce.

"Whatever we can't produce, this is where the community is involved," Juan explains. "The ripple effect becomes: if you can sustain yourself and provide for others, you can create an economy that's more stable and sustainable."

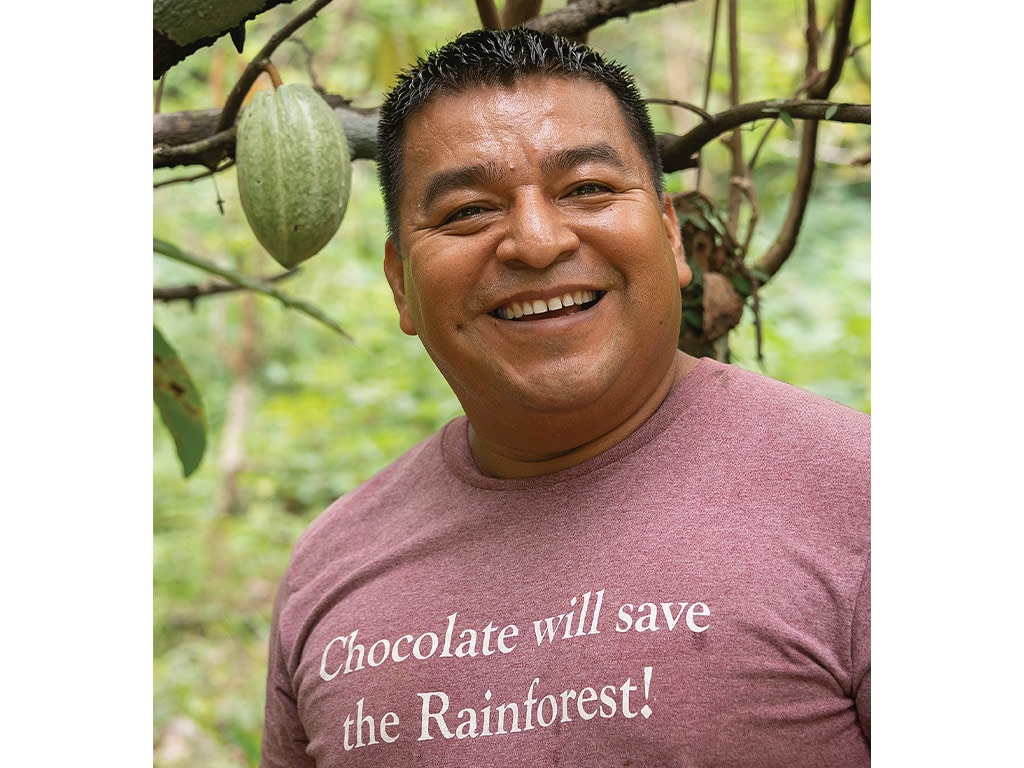

Above. Cho demonstrates old-school cacao processing. Most of the Chos' cacao beans represent the native criollo variety. Abelina Cho's catering for agritourists creates a market for local produce. Cacao, citrus, and chiles from the Chos' farm are the basis of their exquisite Ixcacao chocolate brand.

Expert farmers. Maya agriculture has been rich and extensive for thousands of years, notes geography professor Tim Beach at the University of Texas at Austin. Cacao and vanilla were prized, and staples ranging from corn to beans, squash, avocados, papaya, cashews, and 400 other crops sustained an urbanized society of as many as 2 million. Working with stone and wooden tools 2,000 years ago, Maya engineers created vast systems of raised fields and canals to drain wetlands for farming and store water for irrigation during the dry seasons. Beach says there is evidence that the canals were also used for fish farming to boost protein supplies.

The resulting wetland fields were massive—Beach led a team that used lidar imaging to discover canal and field networks spreading over more than 15 square kilometers (3,700 acres) in northern Belize.

"This is a very diverse, very sustainable, very complicated form of agriculture practiced by people who carried a huge amount of information in their minds," says Beach. "They were multi-cropping. They were cropping different lands and managing water to get away from hit-or-miss drought. They were cropping different crops because they knew they had pests to deal with as well."

The engineered wetland fields of the Maya form a foundation for modern commercial farming of rice and corn in Belize, Beach notes. And though historians have long referred to the mysterious abandonment of the great Maya cities about 1,200 years ago as a "collapse," Maya people continued farming those ancient fields into the 20th century.

Like the Chos, many Maya are still on the land. And though cities and many fields have been swallowed by forest, Juan Cho believes tourists' eagerness for sustainably grown food creates a path to the future.

As a money-making crop at the heart of a diverse agricultural and economic ecosystem, says Cho, "chocolate will save the rainforest." ‡

Read More

AGRICULTURE, EDUCATION

Sunny Outlook?

Weather forecasting has come a long way.