Agriculture, Education April 01, 2025

Connected by a Thread

Fibershed ties together regional economies.

by Steve Werblow

"Locally grown" doesn't just have to be about food, nor does it have to be about small scale. Rebecca Burgess, founder of Fibershed, sees the power of tying together the fortunes of fiber producers—wool, mohair, cotton, and more—and spinners, dyers, textile manufacturers, and clothing makers to revitalize regional fiber economies. It's a concept that has taken root in more than 70 communities worldwide.

Burgess has always been captivated by complex systems like watersheds and foodsheds. At the University of California, Davis, Burgess took a weaving class. Working with polyester yarn got her goat...and got her thinking.

"I was contemplating the texture of running plastic through my fingers and being like, 'I'm in an ag school. There's got to be something that we could weave here that's not plastic. Why are we not connecting dots between the material culture and the land?'" she recalls. "I just started building that bridge from weaving back into ag."

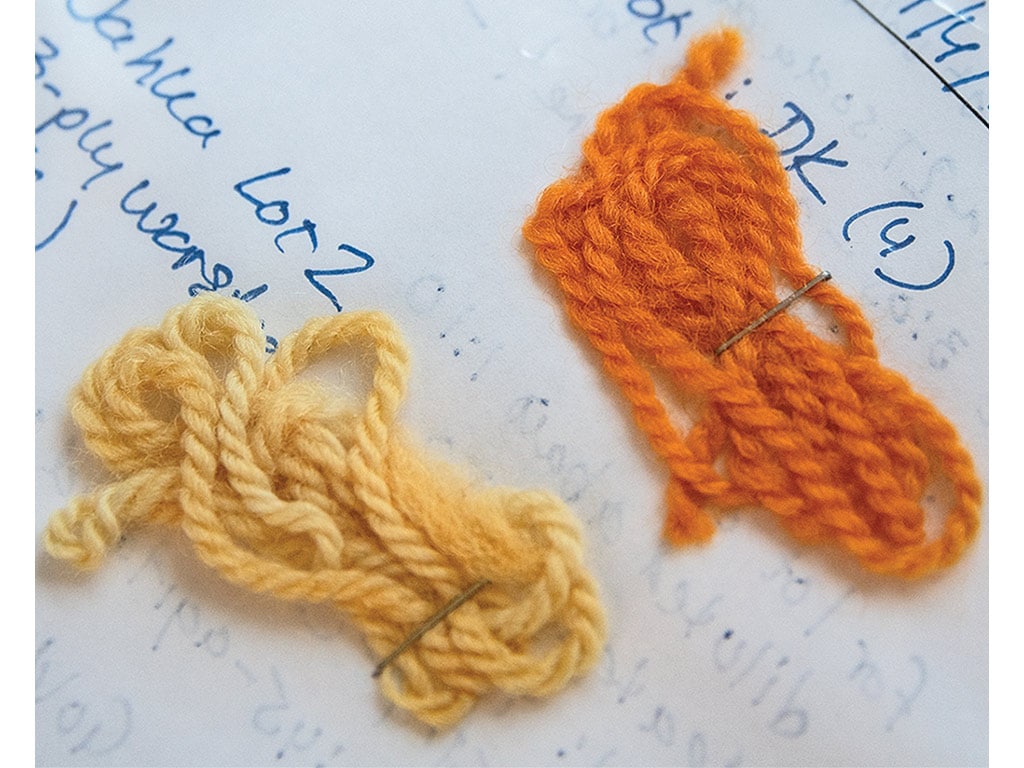

Above. Barinaga Ranch overlooks Northern California's Tomales Bay. Conservation practices on the ranch protect the watershed and build soils. Moorit coloring like this is a key goal of breeder, fiber producer, and microbiologist Marcia Barinaga. Marcia Barinaga moved to fiber after years of producing Basque-style sheep cheese on her California ranch. One of Barinaga's beautiful fleeces. Barinaga keeps meticulous notes on each of her dye lots. Indigo leaves steep.

Walking the walk. Burgess became the proof of her own concept. She learned to spin yarn and make natural dyes from local plants. She gave away her clothes and started creating a new look—and a new outlook—with materials sourced from within 150 miles of her front door.

"That's when I became a guinea pig for the concept," she says. "The land opened up the way we would think about a foodshed map: 'Here's the grain mill here, the grain growers, the distribution and aggregation lines. Here are the new, beginning farmers who want to get into the work.' You end up understanding there's this whole ecosystem."

Burgess introduced design students to farmers and fostered innovation and capstone projects. She engaged cottage-scale artisans and brand managers for huge companies, many of whom flock to Fibershed's 40 acres outside Nicasio, California.

The farmstead is a showplace, a garden, an education space, and a place to think bigger. Native grasses and chaparral on the slopes create a khaki backdrop for a garden bursting with gladiolas, coreopsis, cosmos, goldenrod, elderberry, Hopi amaranth, and even Diné corn, all ready for the dye pot. Indigo leaves steep in a barrel of water, and drying marigolds and stems of weld are strewn across the floor of the garage that serves as a dye studio. Outside, a mixed flock of 70 Jacob and Churro sheep, plus a handful of goats, mill around their nighttime corral. Two shepherdesses manage the flock according to an adaptive grazing plan. A few yards away, staffers closely examine the fate of textile waste in a compost pile.

It's a microcosm of Burgess' vision for tackling huge issues.

"We're surrounded by a waste crisis, an overproduction crisis, and a disinvestment in rural communities crisis, and all of that is driven by faster forms of fashion that are frictionlessly producing high volumes because they can rely on $1-per-kilogram polyester," she explains.

The key is getting more money to farmers, she says, while building an infrastructure to buy and use the natural fiber they produce. Designers, would-be plant managers—many educated at North Carolina's Gaston College, notes Burgess—and 45,000 garment workers currently on the job in Los Angeles alone could put American fiber to work.

Burgess notes that there's room for committed shoppers to make a difference.

"Growers often make 4% of the value of a pair of jeans," Burgess notes. "We really need to undergird the resilience of these farms. Cotton growers in California are asking 60 or 75 cents more per pound. Wool growers are saying maybe 50 cents per pound. That's all they really need to be able to say, 'I can invest in a water system that can help me do better rotational grazing,' or 'that helps me stay in business and helps my kids take over,' or 'that helps me do the match for the NRCS conservation grant.'"

Marcia Barinaga and her husband Corey have put their wool proceeds to work on rangeland reseeding, cross-fencing, spring water development, windbreaks of Monterey cypress, carbon sequestration, and more.

That's great for their stunning 820-acre ranch near Marshall, California, and for the Romney, Corriedale, and Como sheep that live on it. It also benefits the cattleman who leases range from them. They're helping boost Fibershed's Climate Beneficial Verification program and priming the pump for grants to help neighbors improve their ranches.

Barinaga sells wool, fleeces, and naturally dyed yarn through barinagaranch.com and at shows. Her nationwide fan base extends well outside northern California, but Barinaga sees herself firmly within the Fibershed movement.

"To me, being part of the Fibershed is about being part of a local community of producers with shared values, who are committed to raising fiber animals in a way that sustains land and community, that respects the animals we raise, the people we employ to care for them, and the land we steward," she says. ‡

Read More

SPECIALTY/NICHE

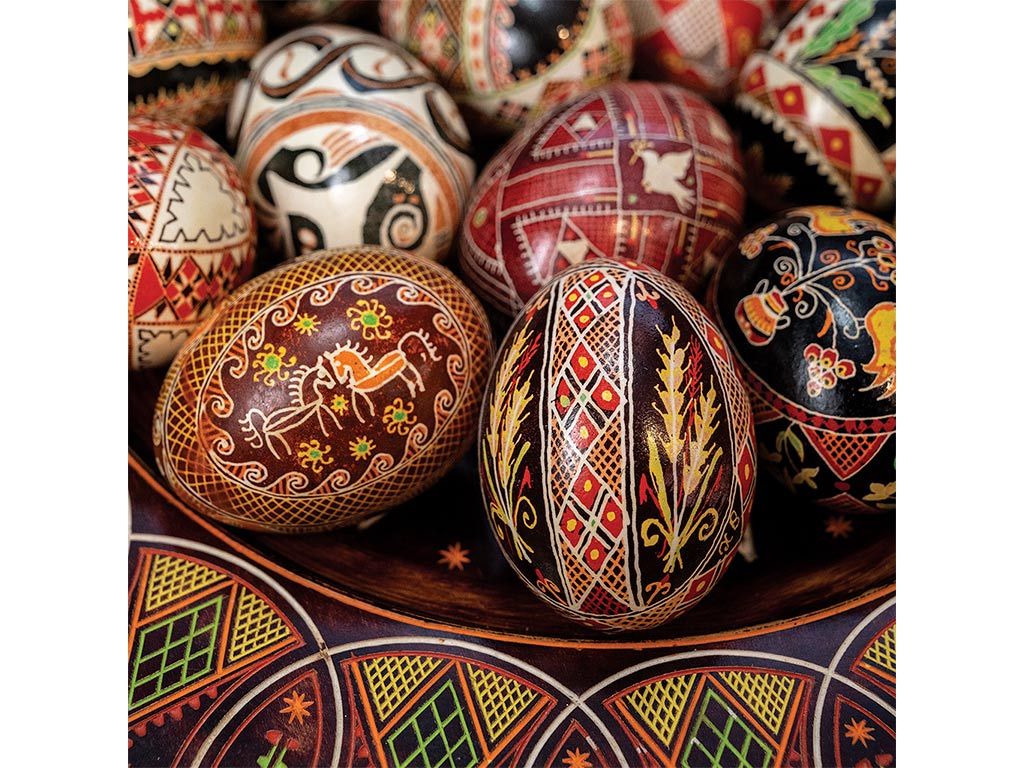

An Eggs-traordinary Art

Ukrainian Easter eggs make family heirlooms and fun.

AGRICULTURE, LIVESTOCK/POULTRY

Home on the Plains

BC couple chases their ranching dream in Saskatchewan.