Specialty/Niche April 01, 2025

An Eggs-traordinary Art

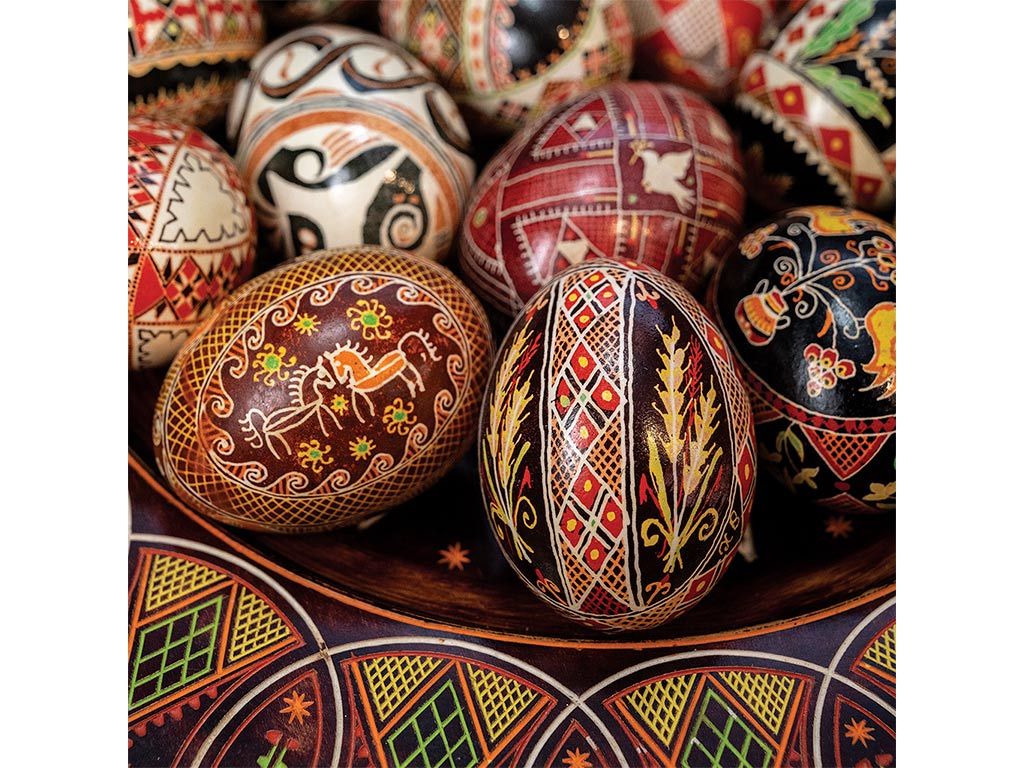

Ukrainian Easter eggs make family heirlooms and fun.

by Martha Mintz

We think of eggs as fragile. Temporary. But in Lisa McDonald's family they are heirlooms; canvases for intricate and individualized works of art that strengthen family and cultural bonds.

McDonald's grandparents were Ukrainian. They met, fell in love, and were married in a German forced labor camp during World War II. Her mother was born in the camp before the family immigrated to Canada after the war.

The young family wasn't able to bring many tangible items on the long journey, but they carried their rich Ukrainian culture in their hearts. Like a treasured possession, their traditions and arts have been practiced, taught, and carefully passed to the next generation.

Ukrainian culture is saturated with colorful, elaborate, symbolic folk art. One of the most celebrated art forms are pysanky, Ukrainian Easter eggs.

From the verb 'pysaty' which means 'to write,' pysanka (singular, pysanky plural) are created by writing on eggs with multiple layers of wax. The eggs are dyed between each layer, resulting in multi-colored works of art.

McDonald picked up her first 'kistka' to write pysanka with her mother and baba (grandmother) when she was just 2 years old.

"My mother and baba were prolific pysanka writers. As soon as the Christmas decorations were put away they'd pull out their TV trays and start writing," says the Casper, Wyoming, teacher.

They would each make between 10 and 20 dozen elaborately designed eggs to sell at farmers' markets before Easter.

"I figured out there are at least 10,000 of my mother's and grandmother's eggs in the world," she says.

Above. A new wax layer is written between each dye. McDonald's grandfather crafted these styluses (kistkas) for her baba. From pysanky to wheat embroidered vyshyvanka shirts to the didukh woven wheat sculptures, traditional Ukrainian items abound in Lisa McDonald's life. A kistka is heated to melt the beeswax used to write pysanky.

Enduring treasures. Pysanky are generally hollowed after decoration and the shells varnished, allowing them to endure for decades. Some of the pysanky in McDonald's collection are up to 80 years old. The oldest chicken egg pysanka found dates to the 1700s or earlier.

The tradition, however, extends thousands of years as evidenced by ceramic, bone, and stone pysanky archaeological finds. The meaning behind the intricate design elements and saturated color schemes adapted with shifts in religious belief and pressures that came with invasions and wars.

At many points in history Ukrainians were pressured to stop practicing their cultural arts, including pysanky. They refused.

"In pagan times it was believed if Ukrainians stopped writing pysanky the earth would be gobbled up by a giant serpent," McDonald says. Today pysanky are part of the Ukrainian Easter tradition.

McDonald has always been immersed in tradition. She lived in a heavily Ukrainian-settled region of Canada, and earned degrees in Ukrainian language and folklore.

"I went to Ukrainian preschool, learned Ukrainian dance and to play the bandura, which is the Ukrainian national instrument. I even opened a Ukrainian bar named Na Zdorovya, which means, 'cheers,'" she says.

Though very comfortable in the culture, McDonald doesn't consider herself a pysanka artist. That's a title she reserves for her mother and baba and their complicated, intricate creations. Her artistic flair emerges in the creation of equally intricate Korovai—Ukrainian wedding bread.

"I love to teach pysanka though," she says. McDonald has taught many classes on the art.

It starts with a clean, carefully selected egg. "I'll sit at the egg cooler forever. It takes sorting about 10 dozen eggs to get a dozen nice ones for pysanka," she says.

Eggs should be free of hairline cracks or bumps that could make the kistka bounce while drawing. "Farm eggs are great. They have thick shells and unique colors."

Any type of egg will work. McDonald has created pysanky from chicken, goose, duck, ostrich, quail, even tiny parakeet eggs.

Most of the design is freehand as pencil marks can't be erased. Beads of beeswax are melted in the kistka and drawn onto the egg.

The first layer of wax preserves the egg color. Working from light to dark, the egg is dyed, more wax designs are added, and it's dyed again. Traditional pysanky designs contain symbolism. Wheat, nets, ladders, deer, and more all have special meanings.

Poppies symbolize joy and beauty and are a favorite for McDonald. She has a tattoo of three poppies in honor of the special bond she shared with her mother and baba. She shares their traditions with her children and grandchildren.

They engage in the fun of egg tapping, a tradition where people tap eggs—not pysanka—together until one breaks. It continues until one remains. The person with the last egg earns good luck.

"We each write at least one pysanka per year and I make a special one for each of my grandkids," she says. They're not all fancy. Her collection includes eggs featuring cartoon characters, sports logos, and other pure silliness.

"I hope one day they'll all have a fishbowl full of pysanky as memories," she says, gesturing to the towering glass container on her counter loaded to the brim with her own treasured pysanky. ‡

Read More

SPECIALTY/NICHE

Bridging the Pacific

Reconstructed Japanese farmhouse in Oregon links two cultures.

AGRICULTURE, EDUCATION

Connected by a Thread

Fibershed ties together regional economies.