Agriculture, Farm Operation April 01, 2025

A Place of Possibility

Somali couple builds their own farm in central Minnesota.

by Katie Knapp

On a crisp October afternoon, Naima Dhore stands in her washing station—a converted carport built by YouTube tutorials—and takes a long breath. Behind her, crops grew in neat rows for months. In front sits a refrigerated trailer turned vegetable cooler. And across the yard, her husband Fagas Salah stains baseboard in the outbuilding that will soon be a commercial kitchen.

A dream sparked in 2016 by the best tasting spinach has finally evolved into the first year farming their own land.

It was not what they imagined for their first season—it was both harder and more hopeful than that.

The Somali immigrant couple's path to this 20-acre homestead outside the tiny central Minnesota town of Dalbo was not straight.

Unlike many farmers, they didn't inherit agricultural knowledge—let alone land—from their parents. Though farming is central to the economy of East African countries like Somalia with most families having at least a garden, their parents were not farmers.

Fagas saw another Somali American post online about farming in Minnesota, and the next day he attended the harvest fair at Big River Farms, an incubator program near Stillwater, Minn.

"I tried their spinach and will never forget the way it tasted," he says, his face flush with the salivating memory. "I got eggs, spinach, and radishes and made breakfast the next morning. No chemicals. Just pick it and eat it. You taste the difference."

Fagas was hooked, and their family's future changed that day.

He had spent years driving semi-trucks across the country, so farming offered a healthier lifestyle. "I used to be away from my family," he recalls. "This keeps me home. I'm working here. I can see my kids grow, and it brings people together."

In the years in between, the couple tag-teamed Big River Farms' Grower Training Program and eventually rented small plots to grow their own produce.

Growing more than food. "The aha moment for me," Naima says, "was noticing that not a lot of people selling at the farmers' market looked like me. I didn't think that was right, and it motivated me to make this more than just a lifestyle for us."

Naima's professional background in cultural education and community building is foundational to her drive to become a farmer.

While scouring the countryside for a farm of their own, Naima started the Somali American Farmers Association (SAFA) in Minneapolis to provide her inner-city community members a place to get their hands dirty and grow food for their native dishes.

She also volunteered with Minnesota Department of Ag's newly created Emerging Farmers Working Group. The outcome was a new state office dedicated to helping nontraditional and historically underserved farmers, like Naima and Fagas, find resources and advice.

After multiple farm offers fell through and countless early morning and late night hours were spent on the road to and from rented plots far from their markets, their next chapter finally started in 2023 where corn and alfalfa had been growing.

Starting from scratch with no infrastructure—no fencing and no well—was daunting and exciting.

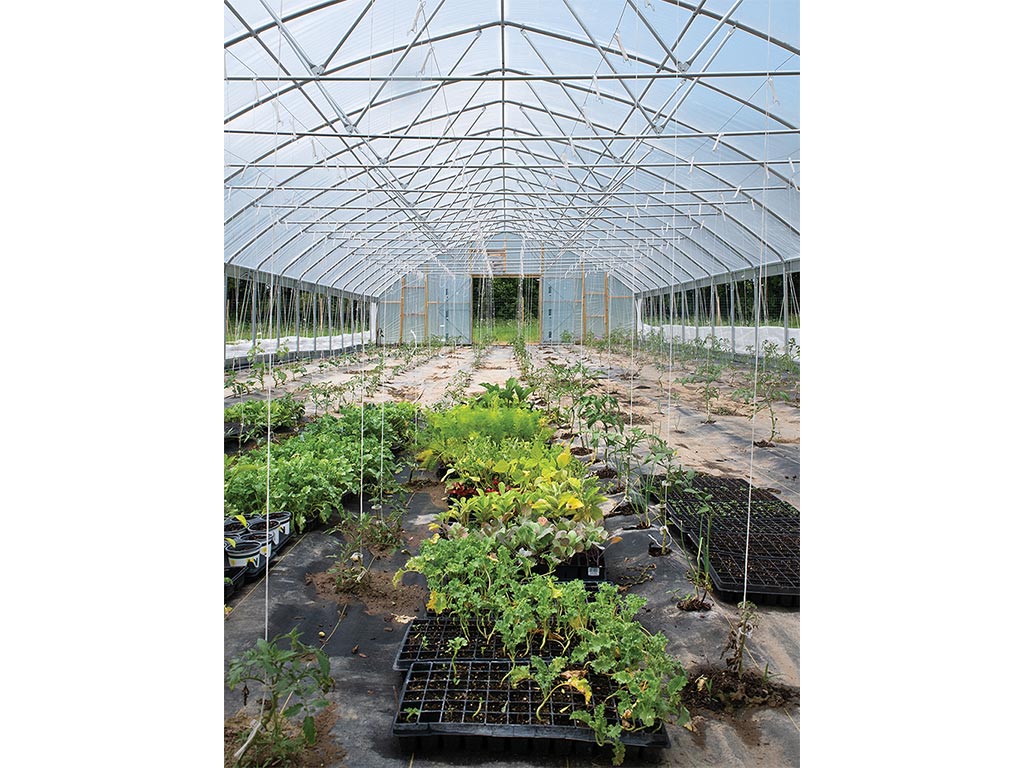

As they finished the growing season at their couple-acre rental property two hours west, they moved into their new house, and Fagas went to work building a high tunnel thanks to Natural Resources Conservation Service funding.

Through the winter Naima navigated permits and contracts.

They secured agreements with a local hospital for the ‘food is medicine' program designed to help fight food insecurity for patients and a food shelf dedicated to providing Halal and other ethnic foods to East African immigrant communities. She also received a value-added grant from the Minnesota Department of Ag to help jumpstart canned chutney and hot sauce sales.

"Everything started to happen fast. It was just Fagas and me building everything," Naima says with a mixture of fatigue and pride. "We are really thankful to finally have a place to build out for the long term."

Above. Naima picks the last of the tomatoes in October. Their season started off cold and wet and was followed by a warm, dry fall. She planted herbs for the hospital boxes in flower pots to help control the spread and add more variety. The lettuce and spinach crops failed, but radishes grew well. While Fagas built key infrastructure, Naima tended to the plants. She planted, picked, washed, and packed nearly every pound. The couple was only able to deliver a fraction of the leafy greens they contracted. At the end of 2023, their farm was acres of alfalfa. By the end of 2024, it had fencing, a well, eight vegetable beds, one high tunnel, a wash and pack station, and a cooling trailer.

Learning the land. Instead of digging furrows, they decided to use a no-till method to kill existing grass and suppress weeds. They covered outstretched layers of wet cardboard with fresh compost and lined the walkways with wood chips.

"Everything will break down, but the process requires patience," Fagas says.

Their goals for the season were to develop eight to 12 outside plots, fill the high tunnel, install irrigation, and build a washing station and cold storage.

Mother Nature had other plans for their ambitious first season.

Nonstop spring rain delayed field prep. Then their first compost delivery came with high levels of boron. "We had to let it wash out," Fagas explains. "That delayed us another month."

As they waited for the skies to clear, they marched on with the seemingly endless to-do list. They knew how to farm, but they didn't know the land yet. Every day something else required creative problem-solving.

They converted washing machines into spinning dryers for leafy greens. Their cooling solution? A used shipping container.

"These new innovations that market gardeners are coming up with are great—we cannot afford a big motor to cool down a whole container," Fagas explains. "So I figured out how to retrofit window AC units."

Many of the low-cost solutions Fagas built came from tutorials he found on University of Vermont Extension's ag engineering blog.

"This is our first home, our first property. There is just so much maintenance to keep up with," Naima said, overwhelmed at the end of July. "We have to give ourselves credit, but I just feel like we still have a long way to go."

The inroads they made with infrastructure projects didn't match what their sandy loam rows produced, though. All season they struggled to find the sweet spot with soil fertility, moisture, and temperature.

When their lettuce crop failed, they could deliver only 50 heads of the 2,000 they'd contracted to sell.

"As a farmer, you accept losses," Fagas reflects. "Sometimes you wonder, why did I choose this lifestyle? And then you remember you have a passion."

Naima, the visionary and planner of the couple, adds, "That's why we're trying to create multiple enterprises. Farming is risky, and there's a lot of potential loss. A few acres of vegetables are not enough to pay the bills. We have to think about other ways to generate income for our family."

Growing forward. Her dream mix is two acres of vegetables including more high tunnels, fruit and tree nuts interplanted between the beds, a few acres of millet, value-added chutney and hot sauces, and a tiny house on the other side of the property for agritourism. She also wants to open the wash and pack station, cold storage, and future commercial kitchen to other small producers.

"Another goal I have is to share our growing space with SAFA members. I want to eventually create an incubator program like what we went through at Big River Farms to help Somali community members raise more culturally specific foods," Naima says.

Her ideas flow as smoothly and energetically as a cup of her homemade Somali tea.

While picking her last box of tomatoes from the high tunnel on that bright fall day, Naima says, "With our experience, some things are so obvious, so familiar. You think, 'I know how to fix this.' Others? All I can say is I know what we're not going to do next year."

A big focus for the next growing season will be on soil health and drainage. And with less build out needed, they will both be able to tend to each crop more thoroughly.

"All the things we're able to do, the infrastructure, the building, I'm really proud. The cash flow still keeps me up at night, but it reminds me that this is an ecosystem. I can't compete with Mother Nature," Naima says. Her spirit finally shines through again after being squashed by the tough season.

Fagas adds, "It just takes a little love." ‡

Read More

AGRICULTURE, EDUCATION

Calibrate Yield Goals

Prioritize profit using soil health to reduce input costs.

AGRICULTURE

It Starts with a Seed

Seed catalogs bring early-season joy to gardeners.