Agriculture, Education April 01, 2025

Another Roadside Attraction

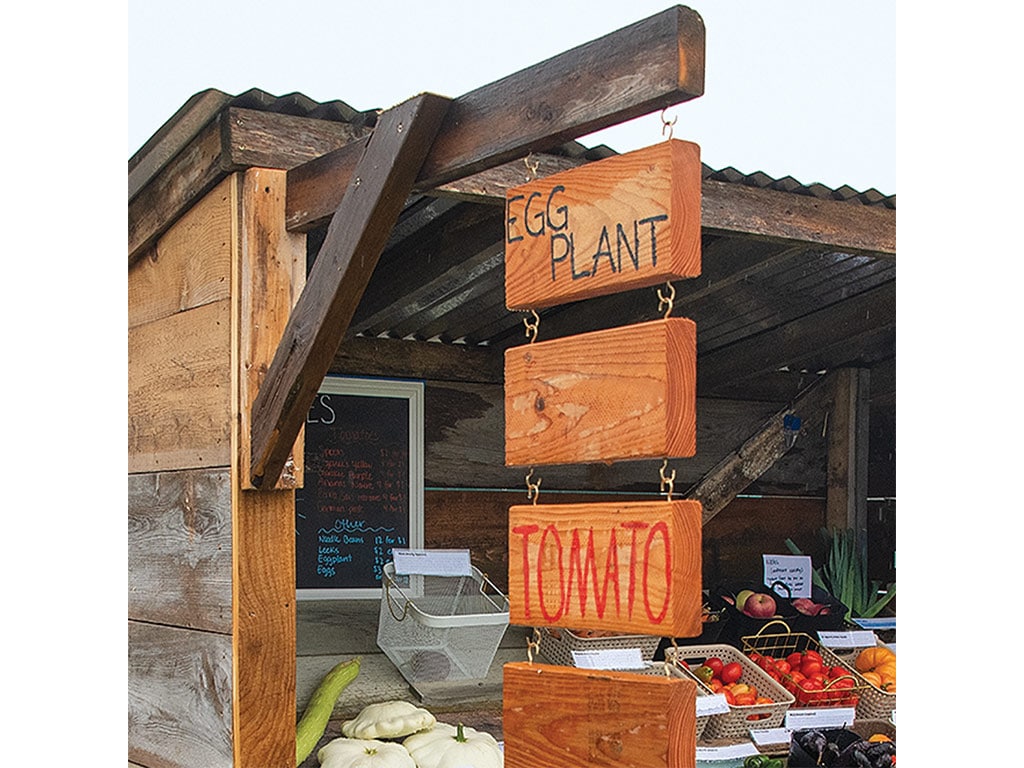

Roadside stands are a window into local agriculture.

by Steve Werblow

Big or small, loaded with gifts and pies or stocked with the morning's harvest of a handful of vegetables, farmstands are the public face of local agriculture. They're the memory-makers of steaming bags of boiled peanuts in Georgia or fresh cherries in Michigan, red strawberries in California, and sweet, sweet corn in Illinois. Farmstands show us what grows a stone's throw from the roadside. They remind us what it means to eat a fruit or vegetable in-season.

"If you can catch people, if you can make them just think a little bit that, 'it's not just food on a shelf or just an apple'—make them think, 'what's the magic here? Is it the season? Is it the color? Is it the flavor? Is it nutrition?'" says Amy Machamer of Hurd Orchards in Holley, NY. "If we can just capture their imagination, then they become engaged with our farm."

Hurd Orchards' roadside shop is a hive of activity along a busy road. Machamer chats with customers across antique bakery cases stacked with exquisite treats. Woven baskets hang from the ceilings, sunlight streams through rainbow-hued bottles of fruit vinegar, and shelves and tables are stacked with gifts and gourmet treats.

Other farmstands can just be a corner of a barn with an honor box, a covered cart on the roadside with a Venmo code, or a parked car with its trunk wide open.

Increasingly, farmstands are not relegated just to county roads or gravel. For instance, the New York State Thruway Authority has teamed up with the state's Department of Agriculture and Markets to host farmstands at highway rest stops. Several of the state's roadside welcome centers have Taste NY vending machines loaded with food from local farms and processors, available 24/7 with just a swipe of the credit card.

Researchers at the Northeast Regional Center for Rural Development and Pennsylvania State University determined that 6% of U.S. farms—116,617 operations—reported some direct-to-consumer sales of edible products in the 2022 Census of Agriculture. Total receipts amounted to $3.26 billion that year, mainly rung up by small and medium-sized farms.

Those direct sales can be a sideline for growers, or they could help keep farms afloat. In Chittenango, NY, population 4,810, the Henry family's farm store draws shoppers from miles away—especially during sweet corn season.

Location. Peter Henry notes that his farm's location on a state highway between Utica and Syracuse has boosted the shop.

"Location is a key with this thing," he says. "If you're in the right place and you've got the right stuff, you'll be OK.

"We started out with sweet corn on a card table," Henry recalls. "We'd make $10 a day. Now we've got a whole building. This started out as a thing to do. Now it's meat and potatoes—we'd be a lot leaner if we didn't have it."

Margins can be good in direct sales, but quality is a must, he says.

"It's not the cheapest, but we keep the quality good and it sells," Henry adds. "If it's not good, there's not a car in the driveway."

The farmstand is the outlet for all the tomatoes the Henrys grow in their high tunnels. Griffin Henry staggers 10 plantings of sweet corn—starting with 65-day varieties and working to 85-day corn—to maintain a steady flow of the farm's big draw. A neighbor named Marlene bakes pies, and salesperson Marva Hogan meticulously stacks ears of corn and rich, red tomatoes in the displays. Buyers peer into the refrigerator to check out the Henrys' beef, chickens from a nearby farm, and cheese from down the road. There are eggs, bottles of maple syrup, and much more.

Henry points out that direct-to-consumer retail is about having plenty of variety—and plenty of help.

"It ain't one guy," he says. "You've got to have everybody working together. And without the whole schmear, it's hard to sell stuff."

Half a world away, in the tiny European principality of Liechtenstein, Christian and Heike Konrad run a similar shop on their 81-acre farm on the outskirts of the capital city of Vaduz. Despite the short season in the Alps, just 13,000 acres of farms and pastures, and a mandatory 14% set aside for biodiversity, Liechtenstein's 100 or so farmers provide their country with 45 to 50% food self-sufficiency.

The Konrads produce milk, beef, donkey meat (their donkey sausage was a huge hit when they introduced it last year, says Christian), chicken, vegetables, and a traditional, purple cornmeal called Vadozner polenta. They are also experimenting with rice, chickpeas, and black beans.

Shoppers wander in whenever the door is open, record their purchases in a school binder on the counter, and leave their money in an honor box.

A few hours' drive into Switzerland, Pascal Gutknecht and his partners at Gutknecht Gemúse (Gutknecht Vegetables) operate 17 acres of greenhouses and 321 acres of outdoor fields. They wholesale to Switzerland's major retail chains as well as to a distributor that serves independent shops. But they also rely on their on-farm shop, the size of a small supermarket, to sell second-quality produce and talk to consumers.

"This store, it's not just an opportunity to sell products, but it's also like a test environment," says Gutknecht through a translator. "We can see first-hand what customers like to buy. We can try a few new crops and see how the customers respond.

"We don't do anything unless we test it," he adds.

Above. Christian, Heike, and Frank Konrad (Leo is not pictured) operate a well-stocked shop on their 81-acre farm near Vaduz, Liechtenstein. A burst of color greets travelers on a country road in upstate New York. Each heirloom variety is lovingly detailed in the tiny signs. Customers leave money in a box or transfer funds by Venmo. Swiss vegetable grower Pascal Gutknecht visits his farm's supermarket-like store a couple of times each week to observe customers and engage in market research. Liza Jane's Farmstand outside of Enterprise, Oregon, sells grass-fed beef from the founder's operation, 6 Ranch, as well as a wide range of other ranch products. Nothing beats a strawberry purchased the day it was picked. The Henrys' farmstand team (from left) includes Antonio Ramirez, Marva Hogan, and Peter, Michele, and Griffin Henry. Taste NY vending machines offer regional bounty 24/7 at this highway welcome center. Former picker Juan Robledo sells California fruit and prepared foods.

Prepared. Back at Hurd Orchards in upstate New York, farm shop sales get a huge boost from a long list of luncheons served in the family's 19th century barn. Rough, pit-sawn lumber contrasts with big sprays of cut flowers and elegant table settings. Every course in the Hurd Orchard team's Michelin-star-quality meal highlights produce from the farm, and many of the recipes—like the old-fashioned ham and the honey oat bread—are actually Hurd family heirlooms.

While guests roll their eyes in delight at the sweet corn custard, the plum jam, and the apple sauce featuring heirloom Tompkins County Kings, Sheila Nealon hops from table to table. She introduces diners to the fruits, vegetables, vinaigrettes, and other ingredients that are available just a few yards away in the shop.

"When we're doing really well, when we have a group that's receptive and that really gets it, the pieces can come together and that can really ignite purchasing," says Amy Machamer, who has hosted on-farm meals and tastings at her family's orchard for 40 years. "That also builds us devoted, 'these are our people' relationships."

Machamer is quick to point out that luncheons and dinners are not the farm's focus, they're a way to connect with neighbors. At the start of each meal, she talks about the farm—its seasons, its history, its flavors—and the food and flowers that brighten the day.

"We're obviously licensed and all that, but we never set out to be a restaurant, and we don't like the word 'venue,'" she notes. "This is an expression. We're trying to say, 'this is us sharing our world with you.'"

Across the country and a world away in terms of scale, Ryan and Erica Idso-Weisz of Itty Bitty Acres in Sams Valley, Oregon, farm just 3.2 acres. Their farmstand is a little lean-to with a single shelf. But it's loaded with produce as well as pickled vegetables, vinegars, jams, honey, flavored salts, salsas, and more. Erica also uses ingredients from the farm in her Mountain Mama Catering business.

"We're focusing on value-added products," says Ryan. "We grow produce, we put it in the stand, we check it daily to make sure everything looks good. If it starts to look like it's going to turn, we store it in the freezer until we're ready to make something beautiful out of it so there's no waste."

Heavy, reusable glass containers minimize waste and link customers to the farm, notes Erica.

"Then they're revisiting and they're bringing something back and they're getting to be part of the cycle, which I think is really helpful," she points out.

Even jars that don't come back help support the business, notes Ryan. "A lot of people in this area, if they have a jar, they're going home and canning whatever produce they bought from us," he says.

One hard lesson the couple learned from regulators is that they—by law—can't include "love" in the ingredient list. Seriously.

But here's the funny part: the best thing about farmstands everywhere is the love. It's in the food. It's in the signs and labels, and in the way the bounty is displayed. Just don't tell the authorities. ‡

Read More

AGRICULTURE

Coming Together When the Lights Went Out

Finding peace amidst chaos left by Hurricane Helene.

AGRICULTURE, FARM OPERATION

Stacking Enterprise

From brewery to bison, this ranch taps every income stream possible.