Agriculture, Education February 01, 2025

The Erie Canal at 200

America's first massive infrastructure project set the stage for agriculture’s success.

by Steve Werblow

The Erie Canal—which celebrates its 200th anniversary this year—put the U.S. on a trajectory to become an agricultural powerhouse, capable of growing and moving crops on a global scale. Just as Northeastern soils were being depleted and the population was looking west for opportunity, the canal tapped the efficiency of water transport to move people and goods across growing distances as the country expanded.

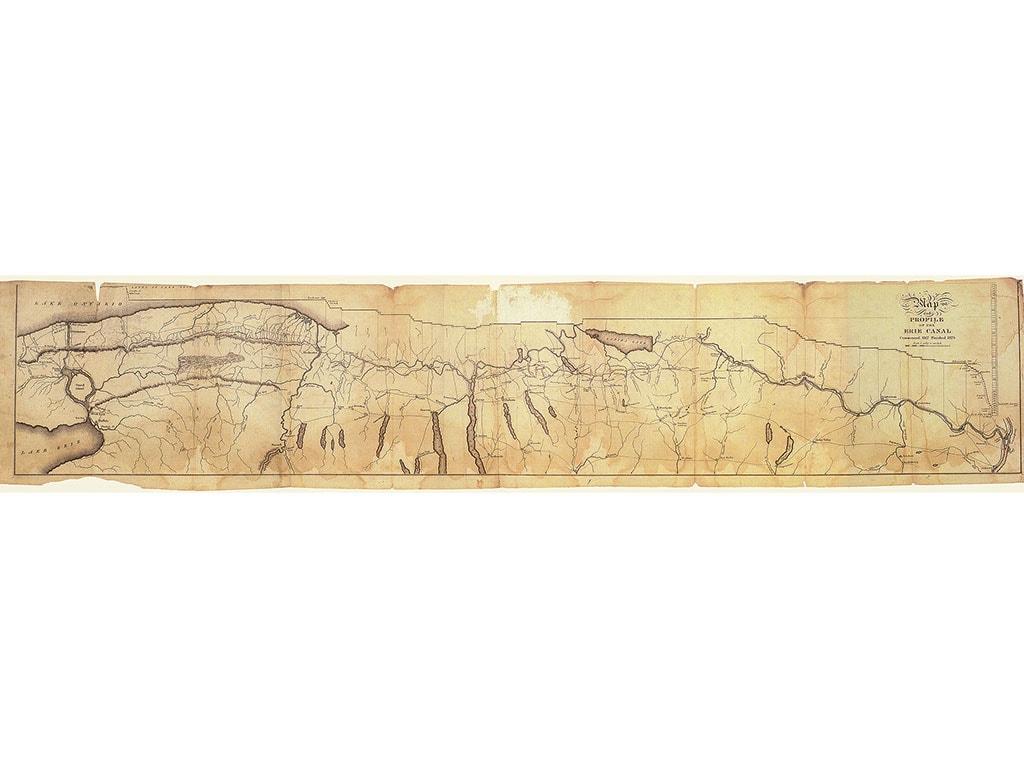

The old reaches of the canal in western New York are quaint: the original dimensions were just 4 feet deep and 40 feet wide. But the project was amazingly ambitious for a country just a generation old, without trained engineers or even a school to educate them.

Using only hand tools and horse power, farmers and hired workers cleared thick hardwood forests, dug through malarial swamps, and built 83 gated mitre locks that lifted boats up and down 675 feet of elevation changes. At 363 miles, the Erie Canal exceeded the length of any of Europe's canals. With the efficiency of floating cargo on water, it opened up today's Midwest, linked New York Harbor to the Great Lakes, and made New York City into the nation's largest seaport.

The success of the Erie Canal gave the young U.S. skills and confidence that set the stage for transcontinental railroads, the Mississippi-Missouri and Columbia-Snake river systems, and the completion of the Panama Canal.

Still, it's hard to comprehend how completely the Erie Canal changed America's agriculture.

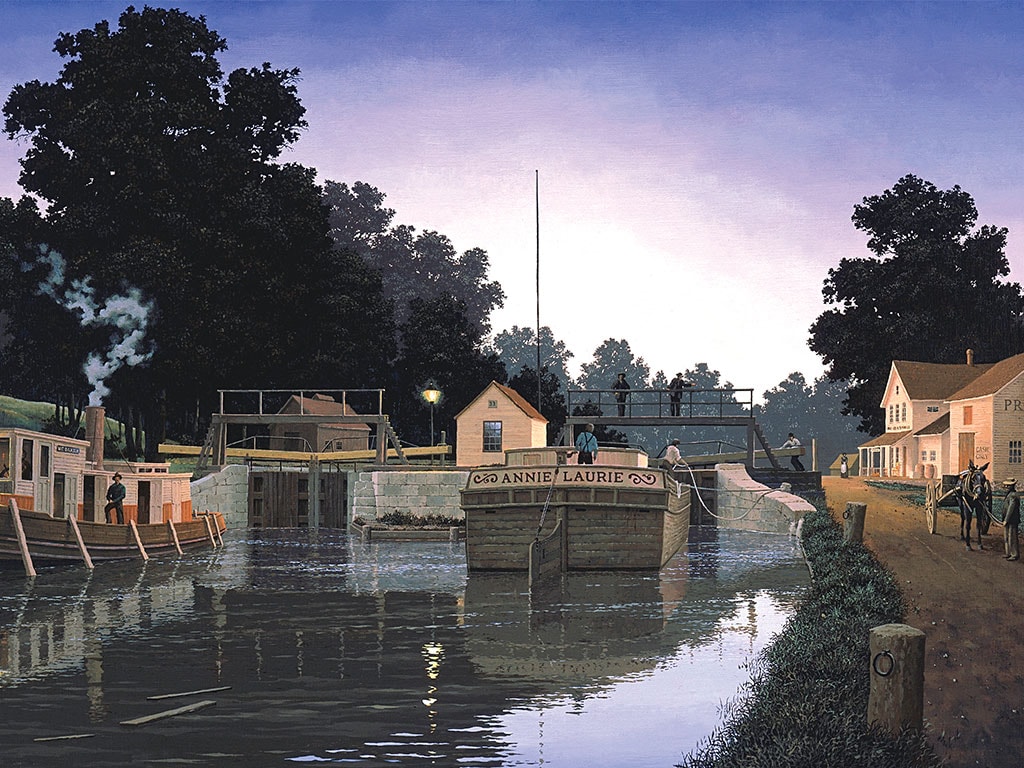

A 6-week walk from Albany to Buffalo, New York, was replaced with a 6-day float. Overnight, freight costs fell by 95% and subsistence farmers turned into commodity producers. Grain elevators sprang up in Buffalo and Brooklyn, and flour mills and canneries spurred overnight growth in frontier towns along the route.

Amy Hurd Machamer is the 7th generation of her family to farm Hurd Orchards in Holley, New York. When news spread that New York was funding the development of the canal, ancestors on both sides of her family moved to the western New York wilderness.

"It was very primitive, it was wild, it was tough. It was a long way from anywhere," Machamer says. "It was days or weeks to get your product to market, so these were primitive, subsistence farms. The day the Erie Canal was completed, there was prosperity just like wildfire across the land. It was overnight prosperity, and it wasn't just in cities—this was prosperity in the countryside. They had virgin land, except what the Iroquois farmed, and they had new markets and growing demand both east and west."

In fact, freight moved along sections of the canal as they were completed, so local booms got underway even before Governor Dewitt Clinton poured two jugs of Lake Erie water into New York Harbor to officially open the canal.

In the Erie Canal's inaugural year of 1825, 565,000 bushels of wheat were barged east, along with 221,000 barrels of flour, 435,000 gallons of whiskey, and 32 million board-feet of lumber.

By 1841, the volume of grain shipments had more than doubled. In 1847, the canal's balance had tipped so more freight originated in the west than the east. And by 1850, 25% of the nation's grain traveled on the canal.

Most of that new wheat was coming from Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and the rest of the growing Midwest, along with iron, wood, and more. Meanwhile, farmers in upstate New York pivoted to higher-value crops. Peppermint in Lyons. Hops in Madison. Cabbage in Phelps. And millions of cans of vegetables and barrels of apples.

Above. The Erie Canal was America's second use of stoplights. Fifteen vertical lift bridges are among 309 bridges built in the 1905-1918 expansion that linked the Erie Canal with New York's other commercial waterways in the statewide Barge Canal. Derrick Pratt is a historian and author at the Erie Canal Museum in Syracuse, New York. Hurd Orchards is just yards from the canal (curving in background). The Medina Culvert, built in 1823, is the only pass under the canal.

Moving people. The banks of the canal also bustled with people on the move. Among them was Walter Brent, another ancestor of Machamer's. He was en route from England to Ohio on a packet boat loaded down with his farm supplies, seeds, nursery stock, and 700 books for his library.

Brent wasn't alone. For years, the Erie Canal escorted a flood of people heading west.

"You've got millions of immigrants coming into New York City and they're heading straight up the Hudson and across the Erie Canal to the Midwest," says Derrick Pratt of the Erie Canal Museum in Syracuse, New York, and author of Erie Eats. "And the Erie Canal gives rise to the first major American tourism boom, as well. It's the first efficient way to get to America's first major great tourist destination, Niagara Falls."

Visitors to the falls were witness to more than just a wonder of nature—they were looking at a key piece of strategy. Canal planners realized a conduit to Lake Ontario would have been a shorter route, but would have benefited the British colonies in Canada. Memories of the War of 1812—and key battles fought along the Canadian border—were still fresh when the route was drawn, putting Niagara Falls squarely between the canal and Canada.

Remarkably, the original Erie Canal was completed on time and on budget, and within just 10 years, tolls collected on the canal had more than paid off the $7.1 million construction cost.

In fact, demand was so great that lobbying to enlarge the canal began almost immediately after the original route opened. In 1836, New York State authorized a canal expansion. Workers augmented the channel from the original 40-foot-wide, 4-foot deep configuration to 70 feet wide and 7 feet deep. The original 90-by-15-foot limestone locks were replaced by double 110-foot-by-18-foot locks to accommodate bigger boats and more traffic.

In all, the expansion increased the carrying capacity from 30-ton packet boats to 240-ton barges.

Above. Bill Sweitzer says the Erie Canal still plays vital roles in tourism, irrigation, fisheries management, and even some freight. This gear diverts canal water to a creek that supplies irrigation to farms. The Erie Canal route cut off Canada from the benefits of cheap transport. Amy Hurd Machamer is the 7th generation in her family to farm along the Erie Canal. The mitre gates of the Erie Canal's locks were designed by Leonardo da Vinci.

Competition. Even as the canal grew, railroads came on the scene and quickly dominated the passenger trade. But for decades, the economics of moving freight by water kept the Erie Canal on top for bulk cargo. In fact, tonnage on the Erie Canal kept growing until its peak in 1880.

Another expansion, authorized by monopoly buster Teddy Roosevelt in 1905 to counter the growing influence of the railroads, linked the state's entire system of canals and lake routes in a 525-mile network called the New York State Barge Canal.

Twelve feet deep and 120 feet wide, the Barge Canal did away with the mule towpath that lined the Erie Canal. Movable dams, which can be lowered during navigation season to maintain canal depth and raised in the winter to let ice and debris flow through, allowed engineers to route canal traffic onto the Mohawk, Genessee, and other rivers. That led to the abandonment of about half of the original Erie Canal channels.

The canal hung on, but the opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway in 1959 routed oceangoing ships through larger channels and sidelined the old Erie Canal.

Today, most traffic on the Erie Canal is joggers and strollers along its banks, and kayaks and pleasure craft in the channel.

But the canal isn't a relic, notes Bill Sweitzer of New York State Canals, the state authority that manages and maintains the system.

"It's a state-run waterway, and we're in the business to help people," Sweitzer says. "It's used for cooling, hydroelectric power, and drinking water in some spots."

Sweitzer adds that the state has worked with farmers and fishing organizations to schedule the filling and draining of the canal to support irrigation and boost habitat and fishing opportunities.

There's still freight on the canal, too. Tim Dufel of New York State Marine Highway Transportation, which operates 10 tugs, says his company regularly hauls rock from quarries in the Adirondack Mountains down to New York City and New Jersey. They've also freighted massive reels of cable and huge electrical parts through the canal system.

Along the canal's route, farms continue to thrive. Amy Hurd Machamer, her mother Susan, and the Hurd Orchard staff harvest 70 varieties of apples as well as berries, vegetables, and cut flowers irrigated with canal water.

Machamer points out that the legacy of the canal and the farms it has nurtured is alive and well. She sees it in the constant evolution of the farms and communities that have been shaped over 200 years by the Erie Canal.

"My mother says the most historic thing we do on our farm—and we do a lot of historic things—is to always be moving to the future," Machamer says. ‡

Read More

AGRICULTURE, SUSTAINABILITY

Slowing The Flow: Desert Water Makeover

Crisis funds pouring into Arizona irrigation upgrades drive wide-reaching change.

AGRICULTURE, EDUCATION

Irrigation Innovation

Technology is driving this farmer’s conservation commitment.