Agriculture, Education January 01, 2025

Ag Espionage

The history of agriculture has stories at home in a spy novel.

by Lorne McClinton

The tea leaves swirl lazily and slowly sink through the hot water as they steep in the Bodum®. Victor Vesely, owner of Westholm Tea Company, Canada's only commercial scale tea plantation, is preparing a pot of Heron's Wake, his signature black tea. A tea connoisseur would describe the red-gold colored beverage as a flowery broken Orange Pekoe with soft undertones of hazelnut and cocoa. It's the culmination of 14 years of Vesely's effort to grow and process an exquisite line of artisanal teas that reflect the unique terroir of his plantation near Duncan, British Columbia.

"Growing up back East I enjoyed tea the way the average person would, in a teabag," Vesely says. "When I traveled to Japan after university, I found that tea was more than just a beverage. It was about gracefully inviting people into your home. It sounds a little West Coast, but tea has a sense. Coffee is about doing, tea is about being. It brings people together. So, many years later I had the opportunity to try to innovate and see what a Canadian tea experience would be. My love and passion for tea became an obsession to share with the world and it turned into a seven-day-a-week business."

Vesely's story is a tale of persistence. He spent years nursing young tea bushes as they adapted to Canada's west coast climate. It's become quite the success, his teas are gaining fans around the world.

His plantation, nestled in a small valley near the eastern shore of Vancouver Island, reflects the mystique of the age-old Japanese and Chinese tea culture that Vesely fell in love with as a young man. Rows of tea bushes rise in sweeping arcs above the weathered cedar tea house.

Above. Cross border intellectual property theft not only hurts victimized companies, it can damage national interests. In 2013 U.S. Customs and Border Protection officers foiled a plot by Chinese nationals to spirit genetically modified rice seeds belonging to Ventria Bioscience of Junction City, Kansas, out of the United States in their luggage.

Common beverage. Tea is the most widely consumed liquid on the planet after water. Billions of cups are enjoyed every day. It's a major crop in many countries around the world, but it wasn't always that way. China was the only country that produced tea into the 19th century and only accepted silver currency for it. It might have remained that way indefinitely if not for what some historians call the Great Tea Robbery.

In 1848 England's East India Company (EIC) hired Scottish botanist Robert Fortune to sneak into China and obtain tea seedlings, seeds, and most importantly the knowledge needed to manufacture tea. The caper was one of the most world changing acts of corporate espionage in history; it destroyed China's tea monopoly.

When people think of espionage, they think about wartime spies or James Bond saving the world. Stealing agricultural intellectual property is never top of mind. In 2011 when Robert Mo (Mo Hailong), Director of International Business of the Beijing Dabeinong Technology Group Company, commonly called DBN, was caught attempting to steal Pioneer Hybrid seed corn, it seemed like a bad slapstick comedy.

In May 2011 a Dupont Pioneer® field manager discovered Mo digging for corn seed in an unmarked research field near Tama, Iowa. Mo claimed he was a researcher from the University of Iowa on his way to a conference. According to court documents when the field manager was distracted by a phone call, Mo fled the scene by driving through the ditch. The FBI later found him by tracing his rental car's license plate.

When the case went to court in 2016, Mo admitted that he'd been part of a years-long plot to steal seed technology. The FBI determined that over time Mo had stolen more than 1,000 pounds of corn seed, representing between five and eight years of research, valued between $30 and $40 million, and spirited them to China. Mo Hailong admitted his part in the conspiracy in 2016 as part of a plea agreement and was sentenced to 36 months in prison.

As bad as this modern case of agricultural corporate espionage was, it paled in comparison to the economic consequences of the EIC's obtaining China's tea secrets. What's nearly incomprehensible to our modern sensibilities, is that the whole plot would never have occurred if not for the strange, symbiotic relationship that developed between the opium and tea trades in the 19th century.

Above. Seren Charrington Hollins' book, A Dark History of Tea, outlines the shady methods the British and the EIC used to break China's tea monopoly. Not only did Robert Fortune obtain tea seedlings, he discovered how tea is manufactured. Victor Vesely's Westholm Tea Company is Canada's only commercial tea plantation. According to the U.S. Department and the FBI, incidents of agricultural espionage and intellectual property theft are on the rise. Just about anyone working on cutting edge technology could potentially be a victim.

A dark past. "Tea has an incredibly dark past," says English author Seren Charrington Hollins. "In the 18th century, tea was grown exclusively in China, and Britain was buying huge quantities of the stuff. But the Chinese weren't keen to buy anything produced in Britain and why would they? We produced lots of plaid fabric and flannel, but they had all this beautiful silk. We had pottery, they had fine porcelains. The trade imbalance though was viewed as a recipe for economic disaster. British taste for tea [some historians say the Industrial Revolution ran on it] was going to bankrupt the country."

Tea was by far the most important trading commodity in the early 19th century. It accounted for 60% of China's economy. By 1800, the EIC's net profits from the tea trade exceeded all other from its Indian empire. So the British weren't willing to keep forking over most of their silver to China. However, the company did find a product the Chinese wanted to buy, opium. The EIC took over the Bengal opium market, helped farmers grow more with new cultivation techniques, and sold it to China. It grew so lucrative that the opium trade soon offset the cost of tea.

It's estimated that 10% of China's population were soon opium addicts, creating major labor problems. The Chinese outlawed it but Charrington Hollins says the EIC just didn't care. They just auctioned their opium to smaller traders, and it continued to pour into China.

"Lin Zexu, an important official in the Qing Dynasty, wrote a letter to Queen Victoria to protest," Charrington Hollins says. "It's uncertain whether she ever got it or just didn't care. In either case China's pleas were ignored. In 1839 China confiscated 20,000 chests (170 lbs/chest) of opium. With very little discussion the EIC took some gunboats and a small army, and defeated the Chinese due to their superior arms. They forced China to open five treaty ports to British trade, including opium."

The loss was catastrophic for China. The Chinese Communist Party refers to it as the start of China's "Century of Humiliation" that lasted until the Communist Party won their civil war in 1949. By the time the first opium war ended though, the British were already working on another plan.

Great tea robbery. They were concerned that China's rapidly growing domestic opium production would soon eliminate the need to import it from India. Since it was unthinkable to have Britain's supply of tea disrupted, Charrington Hollins says, the EIC decided to steal China's greatest trade secret and establish tea plantations in the Assam and Darjeeling in India instead. They commissioned Robert Fortune to go under cover on a three year mission to pull it off.

Fortune disguised himself as a Chinese official and headed off to the hinterlands on his mission. He was taking a big risk. Foreigners weren't permitted to go more than one day's travel outside of the newly opened treaty ports in the aftermath of the First Opium War. If he was discovered it would have likely meant certain death.

History shows he was successful. Fortune became the first westerner to learn that all teas came from just one plant. He somehow convinced tea factory supervisors to show him their manufacturing secrets and smuggled it back to India.

"Tea production quickly established in India," Charrington Hollins says. "It's incredibly labor intensive. Since slavery was banned across the British Empire in 1833, the EIC had to find alternative sources of workers. They were very money oriented, so they devised dreadful contracts that bound their workers for a period of time with conditions that were only slightly better than slavery.

The world quickly felt the impact of the Great Tea Robbery. By 1860 more than 50 British companies were producing tea in India. In 1879, over 70% of the tea sold in England still came from China but by the turn of the century its share had dropped to just 10%.

"I don't think it's really possible today to fully wrap our heads around the idea that the British Empire's government, in collaboration with the Empire's major company, became the biggest drug dealer in the world," Charrington Hollins says. "This led to China developing the biggest drug problem ever experienced by any nation, just so the English could gain that cup of tea. Then on top of all that, they hatched an elaborate plan to steal the tea trade. As incredible as this seems now though, that's exactly what happened." ‡

Read More

AGRICULTURE, SUSTAINABILITY

Sweet Music

Together, soil health principles form a lovely tune.

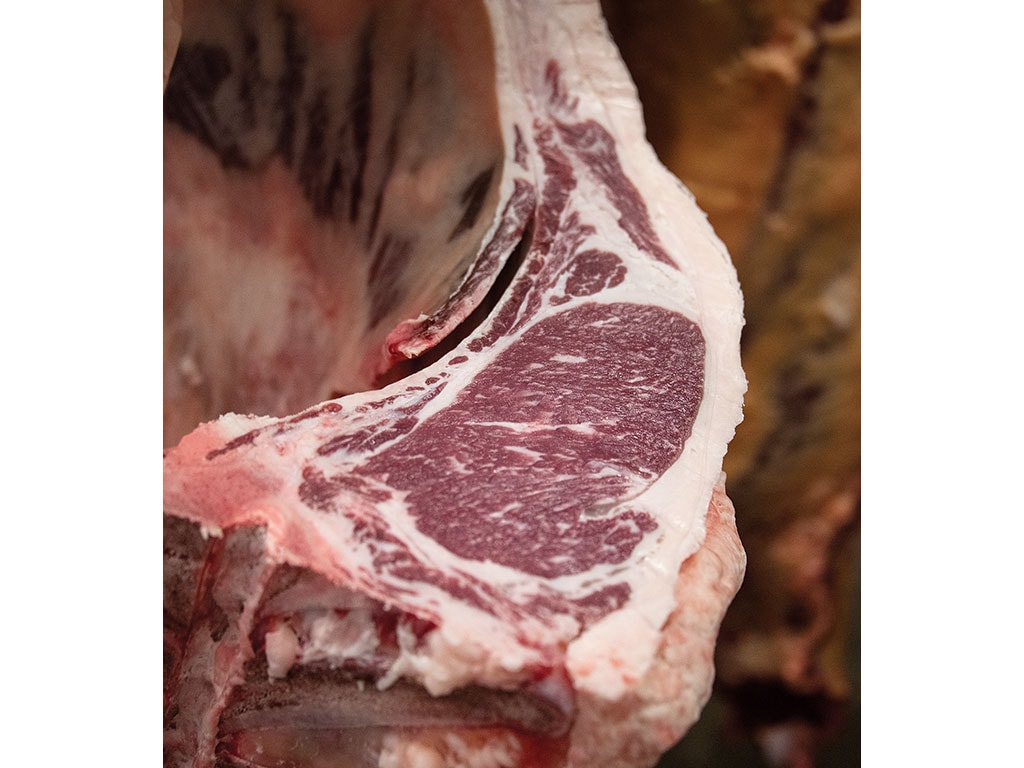

AGRICULTURE, LIVESTOCK/POULTRY

Remote Grading

USDA pilot program can boost small slaughterhouses.